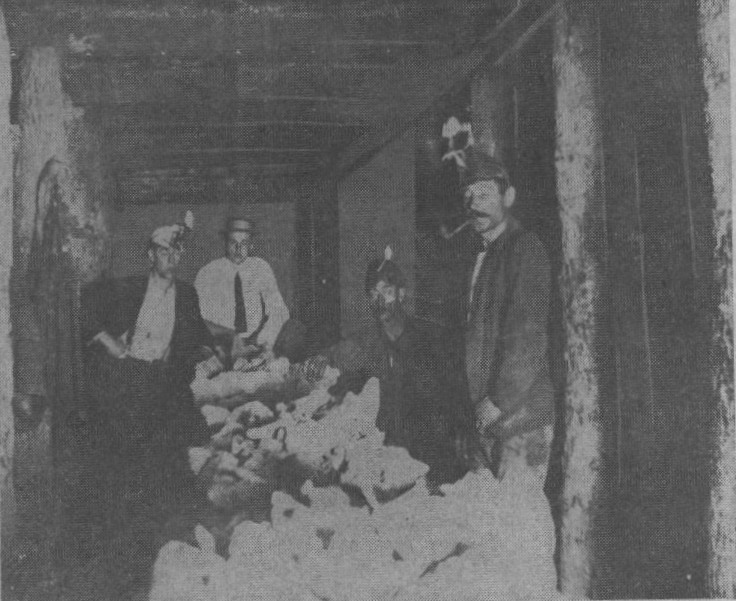

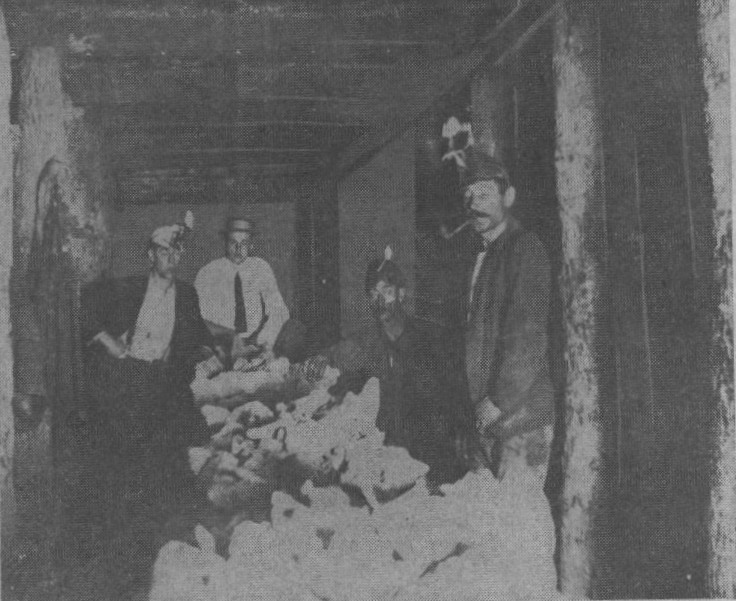

Workers standing alongside clay carts in one of the Highlands Fire Clay Co.'s tunnels under the old Forest Park Highlands in 1908.

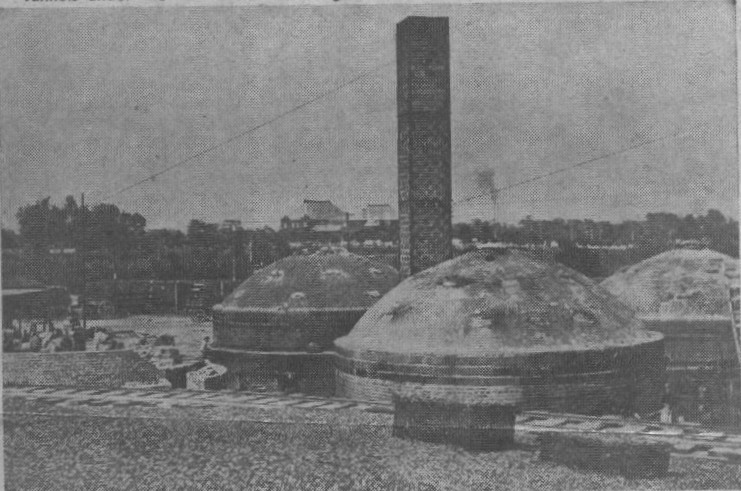

View of kilns at the firm's facilities on the Highlands property

The brewing and milling industries have contributed greatly to the economy of St. Louis for many years, but other industries were important in establishing the city. One of them is the mining of clay and the manufacture of clay products. The clay business began here in 1844 when James Green, a contractor and furnace builder, opened a clay mine in what was known then as the Valley of Des Peres.

Long before it was known or l even suspected that there were extensive deposits of clay beneath the city, William T. Christy, a dry goods merchant, had a well dug on his farm on Morganford road.

One of the workmen digging the well, an Englishman who had been in the pottery business in England, struck clay at about 40 feet. He recognized it as a probable fire clay and drew Christy's attention to it.

Start of Christy Works

Christy started a clay plant in 1857 and later his son formed the Christy Fire Clay Co., which became part of Laclede Christy Clay Products, now part of the Refractories Division of H. K. Porter Co., Inc.

By 1906, a number of clay mining firms were at work in the city and county. The city was honeycombed with more than 70 miles of tunnels, with at least 20 miles of tunnels in the county.

In the remote areas of the city at that time, 4000 workers labored day and night below the ground. The clay was hacked out of seams with picks and shovels, and loaded on mule-drawn carts. At that time, 460,000 tons were produced annually.

St. Louis city and county were in the geological district known as Cheltenham, which is said to have produced the finest clay in the world.

The district was mostly west of Kingshighway and south of Forest Park. It was about a mile wide and extended four miles southwestward to a line running south of Clayton.

A great variety of clay products was manufactured from the clay deposit, ranging from building brick to fire clay products.

Among the various clays mined at a depth of from 60 to 120 feet was fire clay which is the most valuable. The work in the mines was so extensive that small villages and towns sprang up throughout the Cheltenham district.

Fifty different brick yards were in operation by 1895. The glow of their 213 brick kilns lighted the night sky as did the 98 kilns of seven fire clay firms. More than three billion common bricks were produced in 1895. Many of them were used for paving streets.

The fire clay deposits of the Cheltenham district centered beneath the old Forest Park Highlands, where the finest quality was mined at the time.

The Highlands Fire Clay . Co., founded by J. M. Thomas in 1865, owned and Mined 35 acres, the most extensive operation in the area.

The firm, which mined the clay for the glass manufacturing industry, worked a 14-to-20 foot-high vein on the "room and pillar" system. The tunnels were dug at right angles to each other, until the mine became a checkerboard network of tunnels.

When the tunnels were completed, large clay pillars remained, and then these were removed. When the day pillars were taken out, wooden beams were cut, causing the roof of the mine to sink slightly. In places, the ground surface settled causing a rolling appearance.

Jack E. Thomas, grandson of the firm's founder, said the tunnels under the old Forest Park Highlands were filled with water to insure safe use of the surface property. He noted that when the supports of a mine tunnel were removed, three layers of bed rock above moved closer together, thus forming a solid base.

Years ago, the surface development of the clay industry covered acre after acre with unpretentious warehouses, factories and storage yards.

Few persons outside the industry knew of the miles of tunnels and shafts that dotted the area. For the most part, the shaft openings were inside buildings of the clay firms.

Clay products produced here became known throughout the world. At night, hundreds of trains, some unknown to St. Louisans, moved in and out of the city carrying clay products to market.

The Cheltenham clay seam made St. Louis city and county the chief manufacturing center of the state for clay products in the early 1900s.

Today there no longer mining operations in the city, but two open pit mines are being operated in St. Louis county and one in St. Charles county. Most clay now is shipped into St. Louis from outlying Missouri counties and other states.

Thomas, who is president of Thomas Mining Corp., and general manager of the Highlands Fire Clay Co., 1129 Sanford avenue, said his firms are operating a high-grade plastic fire clay mine south of Ellisville, and a shale and fire clay mine in St. Charles County.

He said the Ellisville mine went in operation in 1933. His grandfather had discovered the deposit in 1888. He said the Ellisville clay deposit is "equal to the Cheltenham clay deposit."

A second fibre clay mine is operated periodically by the Refactories Division of H. K. Porter Co., Inc., at Grover, Mo., in St. Louis county.

Thomas, whose grandfather invented what is known as washed pot clays -- freeing clay from impurities -- estimated that the St. Charles mine would last at least 100 years.

Recalling earlier mining days, Thomas said many persons feared the mining operations under the city, complaining that the work would cause sinkage and damage to homes. To disprove this, Thomas built apartment buildings on Sanford between Oakland and Clayton avenue before World War II. He said the area beneath the apartments had been mined extensively, but through proper mining procedures the land has not settled since the apartments were built.

"We built this project to show that mining people aren't so bad," he said. Thomas said some mining concerns years ago "took out every pound of clay." He said timbers were left in place and eventually rotted and collapsed, causing the ground to sink.

Thomas said his firm operated the last mine in the city, which was at Louisville and West Park avenues. It was closed in 1939. There still are deposits of clay in the city but they were never mined because an ordinance was enacted by the Board of Aldermen preventing any further mining in the city. The largest amount is under Forest Park. A number of clay firms attempted to obtain permission to mine under the park, but residents and neighborhood groups opposed the effort.

Clay workings years ago extended out as far as Creve Coeur lake. Several mine shafts were sunk as far north as Natural Bridge road.

The clay mining business here lead to the development of the refractories industry in Missouri, which has continued to grow over the years. Last year, 2,226,000 short tons of clay were produced, with a value of $5,439,000, the Bureau of Mines, reported. This compares with 1,966,000 short tons produced in 1964, with a value of $4,874,000.

Several firms are operating clay products firms here today, contributing a substantial amount to the present-day economy. Thomas said more ways are being discovered all the time to use Missouri clay.

| HOME | DOGTOWN |

| Bibliography | Oral history | Recorded history | Photos |

| YOUR page | External links | Walking Tour |