How much do you know about old St. Louis? Can you locate the places, all within the present city limits, where

One answer will do, because all those descriptions fit the same area. Originally, it was known as Sulphur Springs. Later, it became Cheltenham. Today, it's just another St. Louis neighborhood.

The River Des Peres has been straightened now, funneled into a concrete ditch or shoved unceremoniously underground, and it is difficult to imagine how it once must have looked.

"A clear crystal stream," one writer called it. "A thread of silver sheen" that "stretched a serpentine course through groves, orchards, farmlands, broken abruptly at intervals by a delightful vista of bluffs, hills and valleys."

The river came snaking down through the wooded hills of what is today Forest Park, swung briefly south and then sharply back to the west, beginning a giant curve that finally took it southeast again on its way to the Mississippi - the same path it follows now but with a lot more dilly-dallying.

As it began its westward turn, the stream flowed through a small valley, and partway down that valley, a bit east of the present Hampton Avenue overpass, sulphur springs bubbled through the bed of the river and from out of its banks. (Which explains, incidentally, why Sulphur Avenue is called Sulphur Avenue.)

By all accounts, it was a delightful spot, and it attracted some of the region's earliest settlers. The area was part of the so-called Gratiot League Square, a square league of land granted to Charles Gratiot in 1798 by the Spanish Governor-General of New Orleans, Don Manuel Gayoso de Lemos. The tract, about 8000 acres worth, was bounded roughly by (to use today's street plan) Kingshighway, the southern edge of Forest Park, Big Bend Boulevard and Pemod Avenue.

Gratiot apparently had settled in the area long before he received the grant. In 1777, according to a newspaper account written in the late 1800s, he built a "mansion" on a hill above the River Des Peres, near a spring that flowed down to the stream. "Herds of elk and deer frequented the spot," went the story, "and plowed up with their hoofs the muddy bottom below."

Gratiot's home seems to have been about half a mile east of the sulphur springs, where the Gratiot family established a camp for persons who wanted to take advantage of the supposedly medicinal waters. The springs seemingly weren't therapeutic enough to save the fur trader Manuel Lisa, who reportedly died there in 1820.

Another of the great men of the St. Louis fur trade, William Sublette, bought about a thousand acres of the League Square from Gratiot's heirs in 1831, including the area around the sulphur springs. Sublette, who had gone with Gen. William Ashley on his famous expedition up the Missouri in 1825 and later replaced Ashley as a partner in the Rocky Mountain Fur Co., had a mansion and four large log cabins built near the springs in 1834.

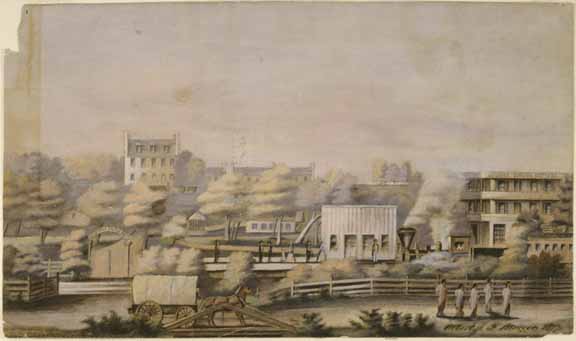

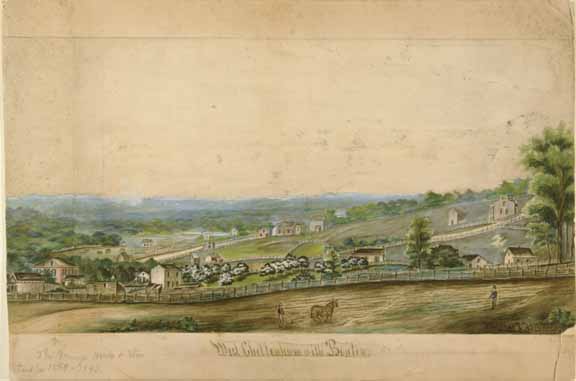

Today, of course, that part of St. Louis, along Manchester Avenue, is all railroad tracks, concrete and factories, and it is hard to say for sure where Sublette's home might have been. In the Missouri Historical Society's collection are four watercolors of the area painted in the mid-to-late 1800s by Albert J.F. Muegge, whose family lived there, and one of them shows the home perched on a hill above the springs. This leads to a conclusion that the mansion was somewhere near what is presently the southern end of the Hampton overpass.

But a newspaper clipping in the Sara B. Hull Scrapbook, also in the Society's archives, tells of a visit to the ruins of the Sublette mansion in about 1878 and places the site to the east of Macklind Avenue, on the edge of what is now The Hill (once known more formally as The Hill Above Cheltenham).

You can follow that writer's path today: "We walk a short distance south on Macklin avenue from the railroad, passing the smelting works (at the corner of Macklind and Manchester) on the left and crossing a bridge over the River Des Peres. Turn to the left, ascend a winding path up the slope (to) a broad plateau of several hundred acres."

That 19th century writer found two massive stone chimneys still standing. The house itself, built of logs (other accounts say the whole thing was stone), had burned down two years before. Now the top of that hill is covered with a jumble of nondescript buildings - an iron works, an auto upholstery firm and other small businesses.

From the hill, there is a good view of the valley below. Today, it could not be called attractive. It is no longer, as it was once described, "the garden spot of the city's vicinity."

Visitors from St. Louis came to Sublette's estate to view his menagerie of "five large buffaloes, some antelope and other wild animals from the Great Plains." They also came for the springs, and Sublette had guest quarters built that were large enough to house 60 boarders.

The Sulphur Springs Resort continued as a popular vacation and picnic spot for St. Louisans after Sublette's death in 1846. The St. Louis Jockey Club held race meetings there, and the resort itself had several owners, including financier and railroad promoter Thomas Allen.

William Wible, who ran the resort for Allen in the early 1850s, owned a country house nearby that he had named Cheltenham, after the English town where he was born. In 1852, when the Pacific Railroad made the resort its first stop on the road west, the station was called Cheltenham, a name that the area had already borrowed from Wible's home.

An article from the Missouri Republican of Aug. 28, 1852, reported that bath houses had just been completed at Cheltenham by "Mr. Hawley of the White Sulphur Springs." It's not clear who Hawley was (perhaps he had taken over management from Wible), but the newspaper obviously approved of his efforts:

"Mr. Hawley has completed his arrangements after a liberal style. Citizens who wish to recruit from the fatigues of these warm summer days must take a drive out. A fine repast and a glass of good wine, (for) those who are merely prostrated; medicinal baths and any quantity of sulphur water for invalids, and plenty of shade, and a pure invigorating atmosphere, to all, cannot but have the effect to draw out crowds."

A view of the Sulphur Springs area in another Muegge watercolor. The resort hotel is on the right, next to the train station. The stone house in the background may have belonged to William Sublette. Whether or not it was his own mansion is another matter, for some accounts place Sublette's home a bit to the east, near Macklind Avenue. (Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society)

The area was also known for the manufacture of fire brick. Deposits of an excellent clay were plentiful in the area, and as early as 1837 Paul Gratiot, the 10th child of Charles Gratiot, had a small fire-brick kiln on Kingshighway, the road that his father had named in honor of the king of France.

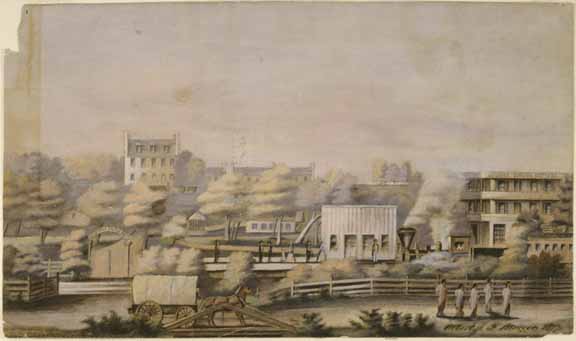

Little of Cheltenham lingers on only on sight depot on the Frisco tracks near overpass. (Post-Dispatch Photo)

The name of Cheltenham lingers on only on this no longer used freight depot on the Frisco tracks nearl the Hampton Avenume overpass

The Laclede Christy Co. established a larger fire-brick factory at Sulphur Springs in 1844, and other firms followed. The Mitchell kilns were built in 1857 and the Winkle Terra Cotta Co.'s factory in 1883. Ironically, the digging for fire clay eventually reached the Sublette family cemetery (the fur trader had asked to be buried on his hill above the River Des Peres), and the remains of the Sublettes had to be transferred in 1868 to Bellefontaine Cemetery.

By the late 1850s, as industry arrived and many new homes were built in the community, the springs themselves became less popular. In 1858, Allen sold his resort to the Icarlans, a group of French communalists who had originally migrated to this country 10 years before.

The founder of the Icarians was Etienne Cabet, the French politician and author who had attracted thousands of followers with his utopian novel, "Voyage en Icarie," published in 1839. Sixty-nine of these Icarians, the advance party, arrived in 1848 in the Red River Valley of Texas to build their new world in the New World.

The Texas frontier turned out to have more difficulties than they had expected, and the survivors returned to New Orleans to join a second group, led by Cabet himself. Nauvoo, Ill., the former Mormon capital, seemed to be a better site for a colony, and in 1849 the Icarians came up the Mississippi by steamboat to settle there.

They did better in Nauvoo, and more colonists arrived from France, increasing the community’s population to more than 500. But in the mid-1850s Cabet was prompted by his colony’s financial problems to become more a dictator than the leader of a communal society. Some of his followers rebelled, and the Icarians divided into "Cabetistes" and "Dissidents."

Unfortunately for Cabet, there were more Dissidents than Cabetistes, and the founder and about 180 loyal followers were expelled from the colony in 1856. They came to St. Louis, where Cabet suddenly died in November of that year.

Despite the loss of their leader, the Missouri Icarians remained together, and many of them took jobs in the city. Two years later, they purchased the Cheltenham property from Allen and moved the colony there. It lasted six years, and, surprisingly, one of the reasons for its disbanding in 1864 was the unhealthy nature of the area.

The little river, unable to support the growth of Cheltenham, had become polluted and brackish, a spawning ground for mosquitoes. The property reverted to Allen and the resort was resumed, but by 1872, the St. Louis Times was complaining that the "cottage and the spring have both fallen into bad repute and the odor of one is nearly as bad as the other."

The railroad had attracted real estate developers to the area, and the hills above the river were dotted with houses. In 1852, a post office had been opened in Augustus Muegge's store at the corner of Dale and Manchester avenues. (The building lasted until 1949.) Supposedly, a farmer named Ulysses Grant often "wassailed" at Muegge's on his trips to the community from his home south of the city.

The Confederate cavalrymen who rode up to Muegge's store on a September night in 1864 may not have known that it had been one of Gen. Grant's favorite watering spots, but they ransacked the store, stole the mail and galloped off into the night before Muegge, who had escaped on horseback, could return with the Union militia.

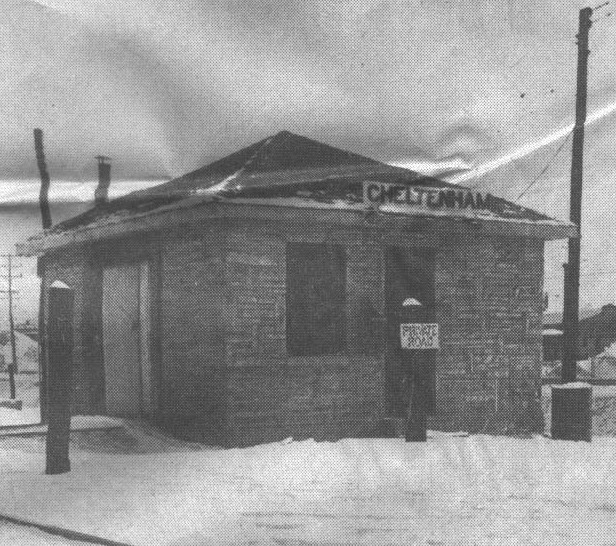

Albert Muegge's watercolor of Cheltenham in 1877 shows a scene vastly different from the present landscape along Manchester Avenue. The fense runs down Tamm Avenue, and the pasture where cows are grazing is now the Scullin Steal Co. plant. (Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society)

In 1876, under a charter that increased St. Louis' size from 191/2 to 621/4 square miles, Cheltenham was absorbed by the city. The "pleasant, desirable country resort" would soon become just another faintly remembered name; the river valley where "Nature has bestowed her favors bountifully" would all but disappear, becoming another of the city's lost landscapes.

=========================

Primary sources for this article are: "A New Look at Old Cheltenham," by George Brooks, The Bulletin of the Missouri Historical Society, XXII, 1 (October 1965), p. 32.

"History of Cheltenham and St. James Parish," by the Rev. P.J. O'Connor, 1937.

Sarah B. Hull Scrapbook, Missouri Historical Society.

"French Icarians in St. Louis," by Boris Blick and H. Roger Grant, The Bulletin of the Missouri Historical Society, XXX,1 (October 1973), p. 3.

A view of the Sulphur Springs area in another Muegge watercolor. The resort hotel is on the right, next to the train station. The stone house in the background may have belonged to William Sublette. Whether or not it was his own mansion is another matter, for some accounts place Sublette's home a bit to the east, near Macklind Avenue. (Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society)| HOME | DOGTOWN |

| Bibliography | Oral history | Recorded history | Photos |

| YOUR page | External links | Walking Tour |