By Henry Boernstein.

(born: Heinrich Bornstein)

303 pages

Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishers, 1990.

Translated by Friedrich Munch in 1852 from the 1851 German original

ISBN# 088286-168-9

Comments by Bob Corbett

November 2003

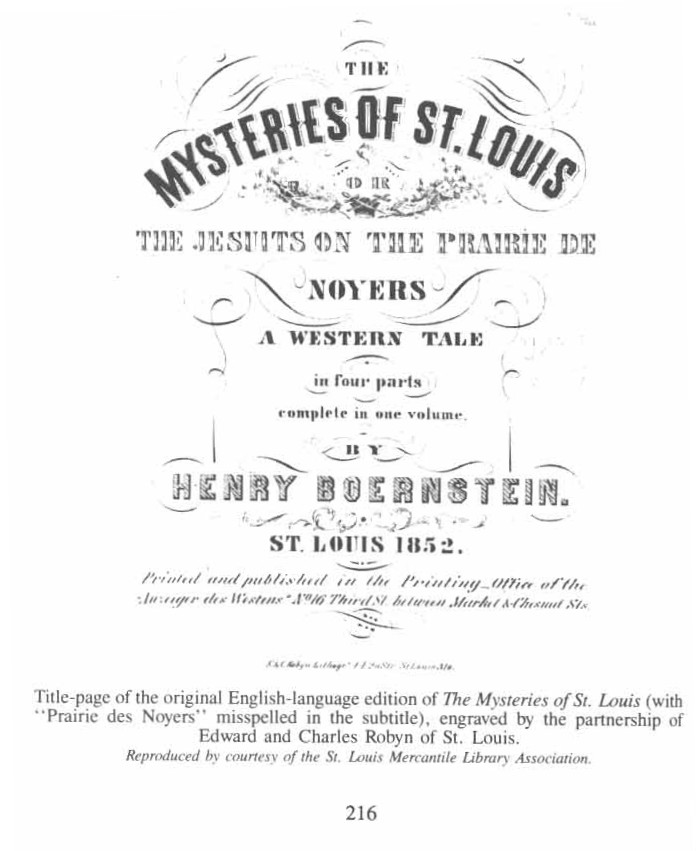

THE MYSTERIES OF ST. LOUIS was first serialized in the German St. Louis newspaper, Anzeiger des Westens in 1851. It was then published as a novel in German, and in 1852 appeared in an English version. The version I read was edited by Steven Rowan and Elizabeth Sims, in which they added dozens of very useful footnotes.

The novel is a classic melodrama in which each chapter ends on some exciting note, hoping to ensure that the newspaper readers will race out to buy the next edition. The evil characters are clearly evil, the good, saintly and simple folks.

We follow the story of the return of the Boettcher family to St. Louis from Germany. Only the old grandmother really remembers St. Louis, from which they fled some 40 years prior. There is great interest in their return, but none of the Boettchers knows this. The grandmother is in possession of a letter from her father talking about an enormous treasure hidden in the Prairie de Noyers (between Grand and Kingshighway). The evil folks, led by the rich lawyer, Mr. Smartborn, are out to get the letter and discover the treasure.

The novel is wildly romanticized with characters whose very names identify their roles, such as Mr. Smartborn himself, his main servant, who echoes the dumbest views of the public, Asa Publicorum, the heavy ruffian who collects past-due rents, Mr. Katchum and so on. The Boettchers, on the other hand, are the kindest, dearest and best people one could imagine, innocent, hard working, loving, caring, ideal humans, workers and citizens.

It’s lots of fun, and, as one might expect, all turns out well in the end; the good are rewarded and nearly all the bad guys are dead, typically not having been killed by the good folks, but sort of bring about their own deaths.

Rowan and Sims add many many footnotes, and the book is a mini-history of St. Louis at the time of the action (1848-1850) which includes such events as the great fire of St. Louis, the cholera epidemic of 1848-50, the role of St. Louis as a staging area for the California gold rush and so on. Many of the footnotes identify the places in and around St. Louis, or clarify activities of the time. In both the novel and footnotes one gets a deeply FELT sense of life in St. Louis at the time: Pictured are the hundreds of steamboats anchored on the river front, the difficulty of fire protection, the muddy streets, the long trips to the near-by countryside of Fenton, reachable only by two ferries and on and on. The picture of St. Louis which emerges from the novel is quite extraordinary.

A sub-theme running throughout the novel is a bitter anti-Jesuit prejudice. That section of the novel is sort of a global conspiracy theory in which the Jesuits are out to subvert the American democracy and make it a property of the Vatican. The central plot surrounding the treasure that the old Mrs. Boettcher knows about is actually a Jesuit treasure of European gold and such brought to St. Louis for safe keeping, but buried in some mysterious place in the Prairie de Noyers. Author Boernstein’s conspiracy goes so far as to hint that the large land purchase in this prairie (the present grounds of St. Louis University) was to hold land in order to search for this treasure.

The author, Henry Boernstein (Heinrich Bornstein) is himself a fascinating character. Born in the Austrio-Hungarian empire in 1805, he is a far leftist anti-capitalist, anti-Jesuit, anti-Catholic journalist who had first run a newspaper in Paris. He was a close friend of Karl Marx and Friederich Engels and published many of their essays in his Parisian newspaper. He immigrated to St. Louis and took over Anzeiger des Westens in which he published his novel. Later he returned to Europe, lived out the rest of his life in Vienna, Austria. He was deeply involved in radical politics and, when in St. Louis, was constantly at logger-heads with Archbishop Kenrich. Just before Bornstein left St. Louis, the two had particularly bitter interchanges over issues that were central to the Civil War.

The novel itself is not much to the literary taste of most of us today, however, it is a marvelous way to get a “felt” sense of life in St. Louis those 155 years ago.

Bob Corbett corbetre@webster.edu| Becoming | Reading | Thinking | Journals |

Bob Corbett corbetre@webster.edu