Bob Corbett

Fall 2000

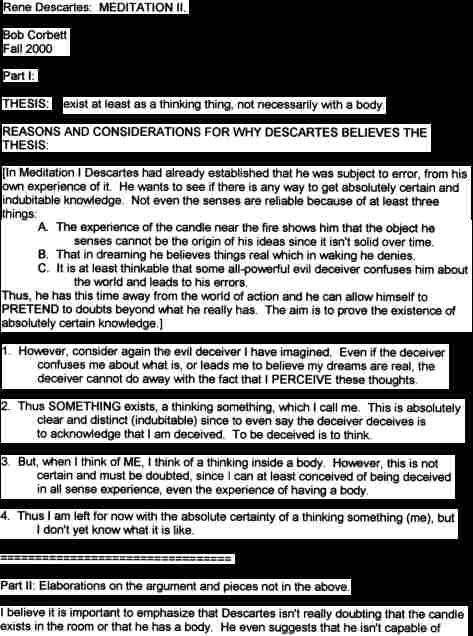

Rene Descartes: MEDITATION II.

Bob Corbett

Fall 2000

Part I:

THESIS: I exist at least as a thinking thing, not necessarily with a body.

REASONS AND CONSIDERATIONS FOR WHY DESCARTES BELIEVES THE THESIS:

[In Meditation I Descartes had already established that he was subject to error, from his own experience of it. He wants to see if there is any way to get absolutely certain and indubitable knowledge. Not even the senses are reliable because of at least three things:

Thus, he has this time away from the world of action and he can allow himself to PRETEND to doubts beyond what he really has. The aim is to prove the existence of absolutely certain knowledge.]

=================================

Part II: Elaborations on the argument and pieces not in the above.

I believe it is important to emphasize that Descartes isn't really doubting that the candle exists in the room or that he has a body. He even suggests that he isn't capable of doubting this. This is a pretended doubt in order to see if he can get some absolutely certain proof of anything.

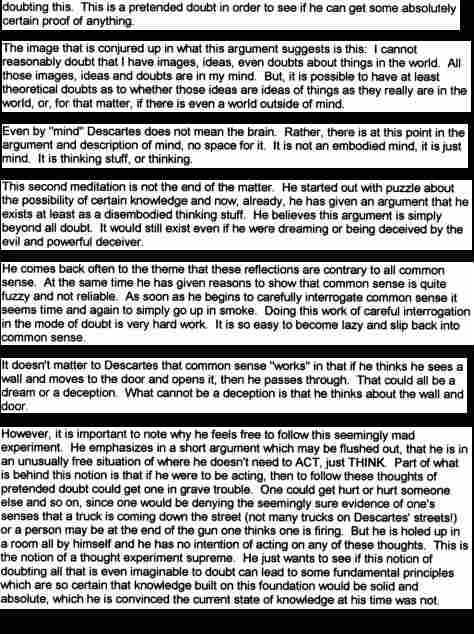

The image that is conjured up in what this argument suggests is this: I cannot reasonably doubt that I have images, ideas, even doubts about things in the world. All those images, ideas and doubts are in my mind. But, it is possible to have at least theoretical doubts as to whether those ideas are ideas of things as they really are in the world, or, for that matter, if there is even a world outside of mind.

Even by "mind" Descartes does not mean the brain. Rather, there is at this point in the argument and description of mind, no space for it. It is not an embodied mind, it is just mind. It is thinking stuff, or thinking.

This second meditation is not the end of the matter. He started out with puzzle about the possibility of certain knowledge and now, already, he has given an argument that he exists at least as a disembodied thinking stuff. He believes this argument is simply beyond all doubt. It would still exist even if he were dreaming or being deceived by the evil and powerful deceiver.

He comes back often to the theme that these reflections are contrary to all common sense. At the same time he has given reasons to show that common sense is quite fuzzy and not reliable. As soon as he begins to carefully interrogate common sense it seems time and again to simply go up in smoke. Doing this work of careful interrogation in the mode of doubt is very hard work. It is so easy to become lazy and slip back into common sense.

It doesn't matter to Descartes that common sense "works" in that if he thinks he sees a wall and moves to the door and opens it, then he passes through. That could all be a dream or a deception. What cannot be a deception is that he thinks about the wall and door.

However, it is important to note why he feels free to follow this seemingly mad experiment. He emphasizes in a short argument which may be flushed out, that he is in an unusually free situation of where he doesn't need to ACT, just THINK. Part of what is behind this notion is that if he were to be acting, then to follow these thoughts of pretended doubt could get one in grave trouble. One could get hurt or hurt someone else and so on, since one would be denying the seemingly sure evidence of one's senses that a truck is coming down the street (not many trucks on Descartes' streets!)

or a person may be at the end of the gun one thinks one is firing. But he is holed up in a room all by himself and he has no intention of acting on any of these thoughts. This is the notion of a thought experiment supreme. He just wants to see if this notion of doubting all that is even imaginable to doubt can lead to some fundamental principles which are so certain that knowledge built on this foundation would be solid and absolute, which he is convinced the current state of knowledge at his time was not.Photo copy of the paper as printed out

Page 1

Page 2

| My Philosophy Page | Webster U. Philosophy Department |

| Philosophy for Children | Critical Thinking | Current Semester | Education | Existentialism |

| Miscellaneous Topics | Moral Philosophy | Peace Issues | Voluntary Economic Simplicity | |

Bob Corbett corbetre@webster.edu