| Contact me | | | Ryan-Dennis | | | Dunn-Timothy | | | Ryan-Timothy | | | Ciaramitaro-MO | | | Ciaramitaro-MA | | | Ireland-Italy |

On an Immigrant's First View of New Orleans

Below are several lines from a travel journal by Rebecca Burlend on arriving at the Port of New Orleans with her family after their two month (2 Sept 1831 to 1 Nov 1831) voyage on an immigrant ship, named “Home”, from Liverpool, England:

“The city is a regular rendezvous for merchants and tradesmen of every kind, from all quarters of the globe.”

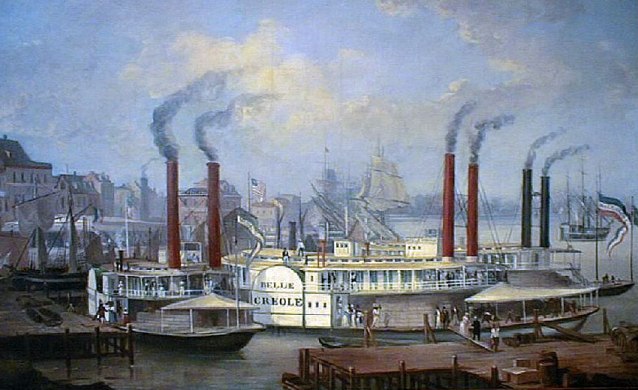

“The (Mississippi) river, which is of immense width, affords a sight not less unique than the city. No one, except an eye-witness can form an adequate idea of the number and variety of vessels there collected and lining the river for miles in length.”

“As a trading post, New Orleans is the most famous and best situated of any in America, but whoever values a comfortable climate or a healthy situation, will not, I am sure, choose to reside there. “

“I must now leave the ship to pursue my route up the stream of the Mississippi to St. Louis, a distance of not less than thirteen hundred miles.”

“The time occupied in passing from New Orleans to St. Louis was about twelve days.”

Left: View across the Mississippi of St. Louis in 1846

On Traveling the Mississippi River to St. Louis in 1848-51

Our Timothy & Mary Ryan and Timothy & Margaret Dunn families arrived 8 Dec 1848 on the immigrant ship, Courier, to the Port of New Orleans (per passenger list). Dennis & Ellen Ryan and family would travel the same route a few years later; Dennis in February 1850 with a large group of Irish laborers, Ellen with their five children in March 1851.

All of the immmigrants, upon reaching New Orleans would need to arrange transportation for the continuation of their journey. One option was to board a steamboat that would take them up the Mississippi River to St. Louis, Missouri, their destination. The other option would be to work their way north over land.

There are no records available that tell us that our Ryan immigrants had the funds to pay the fare for a steamboat ride up the Mississippi. However we trust that they knew what their options would be at that point. And that given they were traveling with their families, wives and children, they would have prepared well for this last stage of their journey.

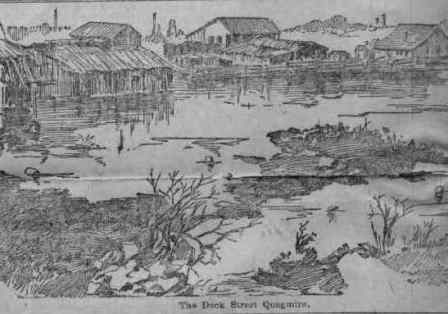

Left: Newspaper image of Dock Street Quagmire

On the Cholera Epidemic of 1848

It’s possible that St. Louis was always their final destination, and that the Ryan Immigrants had other family members awaiting them here, but St. Louis would prove to be problematic in their first years here.

We know not when or how the Ryan immigrants learned about the epidemic that some say positively devastated the City of St. Louis. Cholera, it seems, wasn’t new to the area, but there were those who described St. Louis in 1848-49 as having “the dampest and worst drained prairie in existence”. Therefore, 1848 would be a simply devastating outbreak, and many hard lessons would be learned as the city identified and then addressed the conditions that were there. Conditions that, if they didn’t cause the outbreak, they certainly served as the perfect climate for the devastating spread of the cholera.

It is certain that few residents or immigrants would have read the report filed by Robert Moore, a civil engineer at the time, stating that “the disease had been brought to New Orleans on emigrant ships early in December, 1848 and in a few weeks was carried to all the principal cities on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers”. He wrote that “a boat arrived in St. Louis on December 28 with no less than thirty cases of cholera among the passengers and crew”. I myself believe that it is a miracle that any of our Ryan immigrants survived those first years.

At that time it was estimated that 70,000 people were living in the crowded city of St. Louis. But this epidemic was so devastating that by the time it reached its peak in August 1849, the city had lost more than 7% of its population, and some say 10%. The Cathedral records alone documented that a total of 3,268 Catholic parishioners were buried from the parish that year.

This might explain why some members of the Ryan Family made the decision to detour from the Port of St. Louis and take the Meramec River to settle in one or more of these outlying areas. Family stories tell of family members who were merchants in the Catawissa and Lamar areas of Missouri.

Left: 1852 Image by Thos. Easterly of the St. Louis Riverfront after the Fire.

On the St. Louis Riverfront Fire of 1849

The cholera epidemic was surely devastating to the city, but it turned out not to be the only tragedy that makes 1849 memorable for the City of St. Louis. There was a fire on the riverfront in May 1849 that would also find its way into the record books.

The newspaper reports said: “At about 9 p.m. on the night of May 17, fire was reported aboard the steamer White Cloud, tied up at the foot of Cherry Street, on the northern fringe of the downtown riverfront.”

That fire spread from this single steamer to one after another of the boats that were moored there. And, thanks to several local boatmen, the river itself and eventually cross-winds, it spread from the boats to the buildings devastating the entire riverfront. The fire was so fierce and spread so quickly that the Old Cathedral was one of only a few riverfront buildings that survived what is now called the “Great Fire of 1849”.

Amazingly, fatalities were limited to only three. One of whom was Thomas B Targee, Captain of the Missouri Valley Fire Brigade. The material losses however, would include 33 boats and an estimated $10,000,000 worth of income producing property destroyed.

On The Irish and "Their Troubles" in St. Louis

If the Ryan immigrants actually did choose St. Louis as their destination, it may have been due to what they heard was a more welcoming attitude toward the Irish here. They might not have heard however, that plenty of anti-Irish and anti-catholic threats had already arrived.

These threats were from what was officially called the “American Party” but became known, by their own members, as the “Know-Nothings”. By the members who pledged to keep “secret” the organization, by answering questions that they “knew nothing” about meetings, activities, etc. This growing “Know Nothings” movement began on the east coast but arrived here and caught the attention of some “native” St. Louisans who resented the Irish Immigrants for what was called their ‘penchant’ for political power. At one time, ‘the movement’ advocated a 25 year residence requirement for citizenship and for holding public office. That and the attempts to influence the voters resulted in election-day riots.

It wouldn’t take long before our Ryan immigrants would experience these threats themselves as some would actually happen at the local (Irish) Catholic Church. In 1848, that would be the St. Louis IX, King of France Church, what served as the first Catholic Diocese west of the Mississippi, known today as “The Old Cathedral”.

*One of the riots actually turned into an armed attack on the Old Cathedral. This attack ended however, when an older Irishman, a veteran artilleryman from Waterloo moved into place a large brass cannon just outside the front door of the church. The attack ended soon after it began, as the "movement" eventually did.

*from the Story of The Old Cathedral, parish of St. Louis IX, King of France St. Louis, Mo by Rev. E. H. Behrmann, M.A. ca 1949

On Their Final Resting Places

No matter the challenges they faced, our Irish immigrants from Tipperary, Ireland who settled here in St. Louis, managed to find jobs and housing, supported and raised families and hardly looked back to the "old sod" as Ireland was called by some. They survived the dangerous ocean trip, disease, the weather and the living conditions. Most even survived what was awaiting them here in that record year of 1849. But I have to believe that they all loved America, St. Louis and Missouri.

We feel fortunate to have records of our Ryan and Dunn immigrant families who are buried in local St. Louis Catholic Cemeteries. Most of them in Calvary Cemetery.

Though there are now 17 different cemeteries managed by the Archdiocese of St. Louis.

Records also exist of those whose remains needed to be moved from the original Catholic Cemetery; Rock Spring Cemetery(1854-1885) located at Sarah Avenue and the Wabash Railroad Tracks. It became badly neglected and so completely devastated by vandals that the city was forced to take it over. Plans were eventually drawn up for all of the remains to be transferred to the newer Calvary Cemetery.

What a struggle it must have been for our immigrant families during those early years in America. We, the Ryan/Dunn descendants, are all grateful for how strong, hardy, and determined our Irish Immigrant Ancestors were.

| HOME | DOGTOWN |

| Bibliography | Oral history | Recorded history | Photos |

| YOUR page | External links | Walking Tour |