| Contact me | | | Ryan-Dennis | | | Dunn-Timothy | | | Ryan-Timothy | | | Ciaramitaro-MO | | | Ciaramitaro-MA | | | Ireland-Italy |

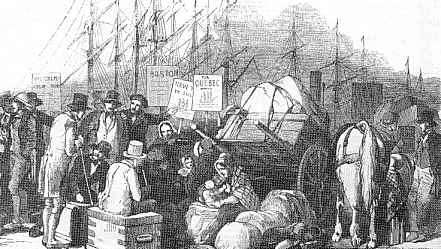

IRISH IMMIGRANT VOYAGES

On “Chain migration”

Traveling singly instead of in family groups was common among the Irish emigrants. There was a process known as "chain migration:" one member of the family would send back money or a ticket so another one could come over. Often the one in America would specify who it was s/he wanted to come over next. Sometimes an uncle or a neighbor would be in charge of bringing over some of the younger children, so the groups that you do find together on the ship lists (when you do find what looks like a family group) are not necessarily nuclear families.

On the Cost of the fare

The price range for steerage passages varied surprisingly little during the century, though competition meant that in any one season fares to north America might range between two and six pounds, and those to Australia between ten and fifteen pounds. The passage price covered basic provisioning for the voyage.... The unsubsidized cost of one passage to America was thus roughly equivalent to the value of a heifer, or the rent of a typical Mayo farm at the end of the century.(D. Fitzpatrick, Irish Emigration 1801-1921 ( N.p.: The Economic & Social History Society of Ireland, 1984), p. 22)

It was even cheaper if you traveled first to Liverpool and then to America, and it was particularly inexpensive to go between Liverpool and Canadian ports (which is one reason some of the landlords tended to dump their tenants in Canada instead of the U.S.).

On Conditions during the trip

Conditions on even the best of the ships were pretty grim. The fare was supposed to include a certain amount of food and water, but there were often complaints that it was unfairly shared out - or withheld entirely - and if the voyage happened to run longer than expected, that was simply too bad for the passengers (and the crew as well).

A typical ticket for the voyage, from Londonderry to Philadelphia, purchased from either ship owner's office [William McCorkle & Company, or Messers J& J Cooke - their records have survived, so this information is available], would state: "We engage that the parties herein named . . . will be provided with a steerage passage with not less than 10 cubic feet for luggage for each adult . . . . Water and provision according to the annexed scale will be supplied by the ship as required by law, and also fires and suitable hearths for cooking. Bedding and utensils for eating and drinking must be provided by the passenger."

On foods and water

The hearths were nothing more than rudimentary boxes lined with bricks, a crude form of barbecue. When the weather was rough, no fires would be allowed, but there would often be a period of calm at the end of the day . . . when a few passengers would be allowed on deck to cook for their families and friends below….

The water ration was supposed to be 6 pints per person per day, to drink, wash and cook. If the journey lasted beyond the estimated period, passengers and crew alike went thirsty and dirty. (Edward Laxton, The Famine Ships: the Irish Exodus to America (New York: Henry Holt, 1996), p. 29)

Emigrants were advised to take along their own stores where possible:

Back to top

On U.S. Laws governing passengers

The laws of the United States require each passenger to be furnished with a weekly allowance of 6 lbs. of meal, 2 ½ lbs. Navy bread, 1 lb. wheat flour, 1 lb. salt pork, free from "bone," 3 quarts of water per day, 2 oz of tea, 8 oz. of sugar, 8 oz of molasses, and vinegar. Children also, under twelve years of age (not including infants) are to be furnished . . . with 7 pounds of bread stuffs per week, including 1 pound of salt pork, half allowance of tea, sugar and molasses, and full allowance of water and vinegar. [note: The law of 1847 . . . states that two children between one and eight years old are to be counted as one passenger . . . ]

It must be remarked, that . . . the amount of provision enumerated above...will not perhaps suffice for the sufficient support of the passenger. Hence, he must in addition buy in a supply of food . . . . (O'Hanlon 30-31)

Back to top

On cooking and eating utensils:

The stores most generally preferred on ship board are potatoes, oatmeal, wheat, flour, fine or shorts, bacon, eggs, butter, &c, in good preservation . . . . A supply of biscuit is in some degree requisite; since the accommodations necessary for kneading and baking bread are indifferent, or rather not furnished, unless by the ingenuity of the emigrant, who must use, for instance, the lid of one of his travelling chests for a kneading board. The same must serve for his table, sitting bench, and other purposes . . . . Knives, spoons, cups, plates, cooking utensils, must be furnished by the emigrants, unless he take passage in the First Cabin . . . .

Back to topOn sleeping conditions:

Bedding is also required, as the berths are unprovided with mattresses, or covering, and usually of such dimensions as will only allow two persons to each . . . . Washing buckets can be procured on board; soap must be furnished by the emigrant. (O'Hanlon 31-32) Many of the ships were not originally intended to carry passengers, but the demand was so great they were hastily refitted. One such ship was the Perseverance, which sailed from Dublin on March 18, 1846.

The crew had cleared the holds, and ship's carpenter James Gray had fitted out bunks four tiers high and 6 feet square. The fare in steerage was L3 (around US $15). In the cramped conditions for 210 passengers, pots and pans to cook their meager rations were a priority, as were a tradesman's tools to earn a living in America . . . .

Back to topOn weather conditions:

In reasonable weather groups of 20 or 30 passengers at a time would be allowed on deck to breathe fresh air for a change, wash their clothing and clean themselves, and to cook whatever rations were still intact and fit to eat. In bad weather they would be forced to remain below, in complete darkness if the seas were really rough. . . . Most of the time they stayed on their bunks; despite the lack of space, it was usually more comfortable there than on deck. The caulking of the boards on the floor of the hold was often slack and the gaps between the planks, as they closed up with the movement of the ship, would catch the passenger's clothing, particularly the women's skirts. Sometimes they would be pinned in one position for hours on end, until the ship shifted in the wind on to a new course. Clothing would be released as the ship went over, although the smaller and weaker passengers might go with her, tossed to the other side of the hold, and become trapped again. (Laxton 12-13)

Back to topOn Coffin Ships:

The Perseverance was not a terrible ship - although all the crew deserted when she arrived in New York - and 1846 was not a bad year as a whole. 1847 was the year of the infamous "coffin ships," such as those carrying the unfortunate (former) tenants of Lord Palmerston. The passengers, already weakened by starvation, some of them already infected by the various famine fevers, crowded into dark and unsanitary ships holds, died in the hundreds if not thousands.

Note: I'd like to extend an overall thank you to all of the various authors and publishers of the many webpages and articles from which I've so freely borrowed for this page.

| HOME | DOGTOWN |

| Bibliography | Oral history | Recorded history | Photos |

| YOUR page | External links | Walking Tour |