SIRE,

In republishing at this period the Life of Toussaint Louverture, I am induced to dedicate it to your Imperial Majesty, by feelings which those who know how to appreciate true elevation of character cannot fail to understand.

That Illustrious African well deserved the exalted names of Christian, Patriot, and Hero. He was a devout worshipper of his God, and a successful defender, of his invaded country. He was the victorious enemy, at once, and the contrast of Napoleon Buonaparte, whose arms he

iv

repelled, and whose pride he humbled, not more by the strength of his military genius, than by the moral influence of his amiable and virtuous character: by how many ties, then, of kindred merit and generous sympathy must he not be endeared to the magnanimous Liberator of Europe!

In nothing, however, will your Imperial Majesty more sympathize with the brave Toussaint, than in his attachment to the great cause in which he fell -- the cause, not of his country only, but of his race; not merely of St. Domingo, but of the African continent.

How would it have cheered the gloom of that solitary dungeon in which this great man resigned his gallant spirit, had he been assured that an arm more powerful than his own would shortly vindicate on his oppressor, the rights of suffering humanity! But could he also have foreseen that with that arm would be found a heart, the seat of every generous affection, a soul ennobled by every elevated sentiment, the unhappy hero would perhaps have lost the remembrance of all his sorrows, while he indulged the animating

v

hope now cherished by every the same sacred cause --the hope that Alexander, the great and the good, having been Providence to restore freedom, justice and peace to one Continent, may, through his powerful influence, soon dispense the same blessings to another.

I have the honor, Sire, to be,

with profound respect,

Your Imperial Majesty's

most humble and obedient Servant

THE AUTHOR

vi is blank.

vii

ADVERTISEMENT.

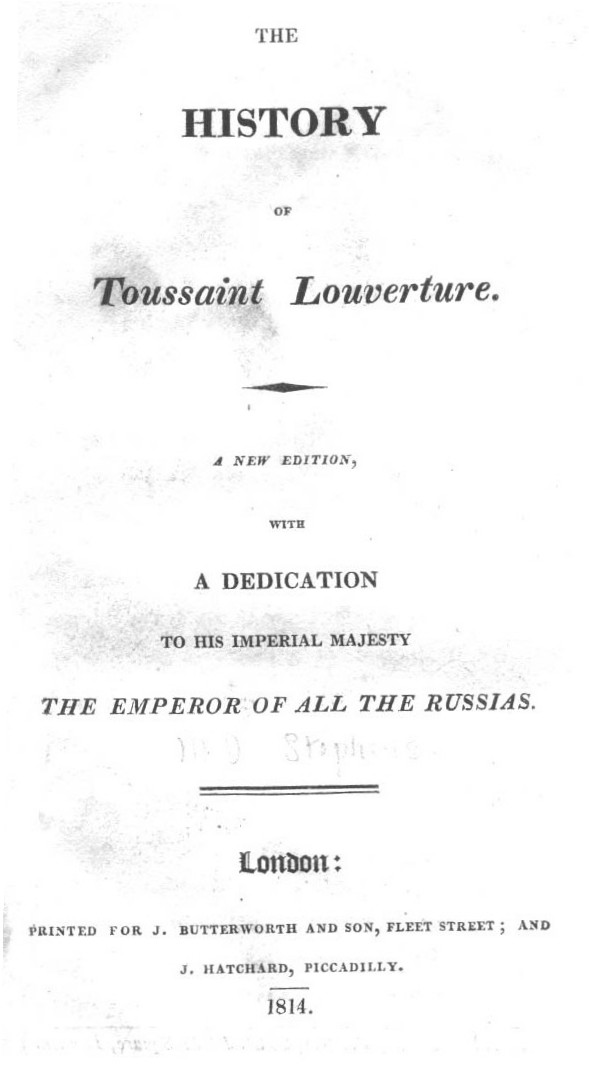

The History of Toussaint Louverture was published in 1803, soon after the recommencement of the war with France, with a view chiefly to its probable influence on the minds of the lower classes of the English readers.

It was designed to counteract the false impressions which many of them had received of the character of Buonaparte; to exhibit him, not as friendly, but irreconcileably hostile, to the freedom of the labouring poor, and to enlist their best feelings against that dangerous enemy of their country, as a monster of perfidy, cruelty, and baseness.

The style was therefore accommodated, as much as possible, to their understandings and taste; but nothing was asserted in it as fact, which the Author did not believe to be substantially true.

Subsequent information has indeed induced him to doubt the correctness of a few subordinate circumstances stated in this little narrative: such as the place in which the illustrious African was seized by the order of Leclerc, and the manner of the

viii

crime; but with these exceptions, the relation is, as he believes, strictly consonant to fact ; and its truth can be in a great measure demonstrated by a careful comparison of the French official accounts with each other, or by more authentic documents.

He has, therefore, thought it expedient not to alter the original form of the work, except by omitting many familiar expressions and allusions which might offend the taste of his polite readers, and some passages and terms, which, in the altered state of our relations with France, could not now used without impropriety.

With these corrections, the Author has been induced again to offer this work to the notice of the public, under a persuasion that its subject will excite new interest when the obdurate resolution of France to renew her Slave Trade excites the afflicting expectation of another attempt to reduce St. Domingo to its former state of slavery. That in this attempt, the amiable and respectable Monarch who now fills the throne of France has not contemplated a renewal of the horrors by which he former expedition was characterized, it is but justice to his character to suppose. There is, however, too much reason to fear, that by whatever delusion it may have been prompted, that odious enterprise has been resolved on: and in assisting the public to judge of the probable consequences, the present publication may perhaps not be without its use.

1

It is not certain where Toussaint was born. Some say he was a native of St. Domingo, and by birth a slave; others, that he came from Africa; and if so, he was born free; for there are no slaves in that country, but what are made such for the purpose of being sold to traders. I incline to think the honour of giving birth to this great man belongs to St. Domingo, but will not stop to give my reasons, as the point is not of much consequence; it, is agreed on all hands that he was in a state of slavery, and that he owed his freedom to the revolution, which took place in that island in the year 1791.

We have no distinct account of the conduct of Toussaint while a slave, but may safely conclude that he was sober, honest, humble, and industrious, because it is certain that he was a favourite with

2

his master, which without possessing those good qualities, especially the two latter, in a high degree, no slave could possibly become. It is also pretty certain that he was a good husband, and a good father ; for it appears that he had, ii opposition to the relaxed system of morality prevalent in that country, early joined himself to one woman, by whom he had several children, the objects of his tender affection; and we shall find that the mother continued to live with him when they were both advanced in years, and to share with him all the dangers and hardships of war, down to the time when he fell into the bands of his treacherous and bloody enemies, and was sent to perish in one of Buonaparte's dungeons.

Toussaint, by the uncommon kindness of his master, or as some say, by his own unassisted pains, learned to read and write; and it appears from his letters and other writings, as well as from his wise conduct, that he made good use of these talents. He probably owed to them in a great measure, the power which lie afterwards obtained over the minds of his,, poor ignorant countrymen; and this, when we find to what good purposes he used his power, will seem an instance of God's gracious providence; for not one Negro slave in ten thousand has the same advantage.

This great man was also prepared for public life by a. good quality more important than all others put together : he was a devout man, and a sincere disciple of Christ.

3

His vile oppressors have called this good man’s religion hypocrisy; but it is not to those impious men who profess themselves Mahometans Turkish countries, that we shall trust for the characters of Christians. They were bound revile his noble heart before they basely destroy him, and they had no course left to take with 1 known piety, but to give it that odious name Toussaint had nothing to gain but the favour God, by openly giving him glory; for his Negroes had been taught little religion, and the people France who had sided with them, were for t most part sworn foes to Christianity.

Though we do not know much of Toussaint private life before the war, I suppose it was spent in a pious, as well as a moral way. It is not like that he became religious all at once when he became a soldier. He worshipped God no doubt private, and in church, when able to go there; and as he added to faith, uprightness and purl of life, he was chosen by Providence to be a lead and deliverer of his brethren. "Him who honours me," says the Almighty, "I will honour."

It is happy for any people, when such persons are raised to public stations. In every place the true staunch friends of liberty, and of the poor must be sought for among those who fear God.

Toussaint had certainly passed the age of for and was probably at least forty-eight, when t great revolution took place in St. Domingo. It too well known that much bloodshed attended that change. The white people first provoked a quarrel

4

with the Mulattoes and free blacks, and in a bloody civil war that followed between those ties, the slaves threw off the yoke of private bondage..

It is no part of my plan to write the history of revolution in St. Domingo, or of the wars at followed it. I know nothing that is to be learnt from the civil wars of that island, but what every well-informed man knows already; I mean the dreadful effects of West India slavery upon the minds, both of the master and the slave. I will only observe, that if the wars were carried on in a very barbarous way, the white colonists were not at all behind the blacks in cruelty; and what is more, first set them the example of it. it is truly shocking to hear of the horrid manner in which those white savages put their prisoners to death, at the beginning of the war.*

* It would swell this pamphlet to a bulk too large, and too costly, were I in general to give quotations in proof of the facts related; but a charge like this seems to call for an authority ; I therefore cite as an instance of such cruelty, an account given by an eye witness, the late Mr. Bryan Edwards.

“Two of these unhappy men suffered in this manner under 41 the window of the author's lodgings, at Cape Francois, on the 46 28th of Sept. 1791." The author then describes the breaking of two Negroes alive upon the wheel; the French mob would not suffer the executioner to put the tortured wretches out of their pain as usual, by a blow upon the stomach; but after he had shewn that mercy to the first, forced him to stop when be was proceeding to dispatch the second. "The miserable wretch with his broken limbs doubled zip, was put on a cart wheel, &. At the end of forty minutes, some English seaman who were spectators of the tragedy, strangled him in mercy. As to all the French spectators (many of them persons of fashion, who beheld the scene from the windows of their upper apartments) it grieves me to say, that they looked on with the most perfect composure and sang froid. Some of the ladies, as I was told, even ridiculed with a good deal of unseemly mirth, the sympathy shewn by the English at the sufferings of the wretched criminals."

Edward's Hist. of St. Domingo, chap. 6. Note on page 78.

It is proper to remark here, that Mr. Edwards was himself a West Indian, and a great enemy to Negro freedom and the abolition of the slave trade.

5

The bitterest enemies of Toussaint have confessed that he had no share in these crimes. This has never been denied by his enemies; and to shew how clear his innocence is, I will here quote the words of an author who is one of his bitterest defamers. Monsieur DUBROCA, who was employed by Buonaparte's government to slander the unfortunate Toussaint, in a libel called his life published at Paris while they were offering rewards for his head at St. Domingo, thus writes:

“Far from taking any part in the movements that preceded the insurrection of the Negroes, he seemed determined to keep aloof from all the intrigue and violence of the times; and certain it is, that history has not to reproach him with taking any share in the massacre of the white people in August 1791." * This unwilling justice ought to have been extended to the whole term of the wars in which he afterwards engaged, during which

* Dubroca's Life of Toussaint, p. 5.

6

not a single act of cruelty can be alleged against him.

Toussaint first rose to notice when the fury of struggle between master and slave was over; his first labours were to protect the white people, who were now in their turn the feeble and oppressed party, from the revenge of his brethren. During the first troubles of the island, our hero appears to have remained quietly at home in his master's service. Perhaps he expected a peaceable change of the state of his brethren from the French Convention; or perhaps he was too pious and humane to join in the means by which the rest broke the galling chains of their private bondage, though lie might see no other way of deliverance. Certain it is, that he was no enemy to the grand cause of general freedom; as might be proved, not only from the great sacrifices lie has since made to it, but from the confidence that was soon after reposed in him by the Negroes at large. It is probable that he was led to remain so long inactive in the war, not only from the mildness and piety of his disposition, but from affection and gratitude to his master; and that these motives being generally known, helped, as virtue will always do in the main, to gain him confidence and support when lie entered on public life.

By the word master we are not here to understand his owner, who, as usual with West India planters, lived in Europe; but the overseer or bailiff of the estate, whose name I think was Bayou de Libertas.

7

By this gentleman, he was treated with kindness, and was a little before the time we are speaking of, raised to a post of no small dignity. My readers may be inclined to smile, but I can assure them that field Negroes would have no feeling less serious than envy, on hearing that Toussaint was actually promoted to the place of postillion.

On our hero's first rising to power among the Negroes, he gave to this master one very pleasing earnest of his future character, which it would be wrong to pass over in silence. The white people, especially the planters, were so odious, both from their former tyranny, and the blood they had cruelly shed in the struggle to preserve their power, that the Negroes, when they gained the ascendant; were disposed to give them no quarter, and happy were those among them who could escape from the island, though it were to go with their families into a foreign country without any means of subsistence. The master of Toussaint, now his master no more, was one of the unfortunate planters who, not having escaped in good time, was on the point of falling into the hands of the enraged Negroes, and would in that event certainly have been put to death ; but his former kind ness to Toussaint was not forgotten. Our hero, at the great risk of bringing the vengeance of the multitude on his own head, delivered his unhappy master privately out of their hands, and sent him on board a ship bound for America, then lying in the harbour. Nor was this all; he was not sent away without the means of subsistence; for this brave

8

and generous Negro found means to put on board secretly for his use a great many hogsheads of sugar, in order to support him in his exile till the same grateful hands should be able to send him a larger supply.

Let this story redden the cheeks of those, who are wicked and foolish enough to say that Negroes have no gratitude. Small is the debt of gratitude which their best treatment under the iron yoke of West India slavery can create; but a noble mind will not scrupulously weigh the claims of gratitude or mercy. Toussaint looked less at the wrong of keeping him in a brutal slavery, than to the kindness which had lightened his chain: and M. Layou was happy enough to find in a freed Negro, a higher pitch of virtue than is often to be found among the natives of Europe.

FThis great man was not long in public life, before he became the chief leader of the Blacks. In their war with the planters they had many other generals, and some of great note, such as Biassou, Boukman, and Jean Francois, all Negroes, and very brave ones. These were famous before Toussaint's name was heard of, but he soon put them all down; not in the Jacobin way, by cutting their heads off, or sending them prisoners to a distant and pestilent country, but as a tall stately tree puts down the weeds and brushwood in its growth, by fairly rising above, and casting a shadow over them. He soon found no equal, without having once destroyed a superior or a rival.

Toussaint seems to have risen by degrees till he

9

came to the chief command, by the growing love and esteem of the people, founded on his good qualities, which unfolded themselves more an more as his power increased. He did not flatter the common people, or encourage them in the crimes, like Boukman, Biassou, and the rest of their leaders.

These chiefs, who were always urging them t revenge and slaughter, and telling them, perhaps that their freedom was in danger so long as White Man was suffered to live in the island, appeared at first to be their truest friends; but Toussaint, who was always trying to teach then mercy, industry, and order, was ultimately found t be the man they could best depend upon; an happy had it been for them had they always followed his councils.

This great man had uncommon gifts both of body and mind: I will mention some of them, an that I may be sure to do him no more than justice they shall be taken mostly from the words of his enemies.

Let us hear, for instance, the evidence of on of Buonaparte's hireling writers before quoted a having published a vile and absurd book to defame our hero in Paris, while the Consul was trying to hunt him down in St. Domingo: Mark how much malice itself is obliged to confess in his favour.

"This celebrated Negro is of the middle stature ; he has a fine eye, and his glances are rap and penetrating; extremely sober by habit, his activity in the prosecution of his enterprizes is

10

incessant. He is an excellent horseman, and travels, on occasion, with inconceivable rapidity, arriving frequently at the end of his journey alone, or almost unattended; his aid-de-camps and his domestics being unable to follow him in journeys which are often of 50 or 60 leagues. He sleeps generally in his clothes, and gives very little time either to repose or to his meals. All his actions area covered with such a profound veil of hypocrisy, that all who approach him are betrayed into an opinion of the purity of his intentions." The Marquis d'Hermona, that intelligent and distinguished Spanish officer, (who had served with our Hero, and knew him intimately) said of him: "If a HEAVENLY BEING* were to descend upon earth, he could not inhabit a heart more apparently good than that of Toussaint Louverture."

I do not copy the abuse that is mixed up with this praise, nor the idle and absurd charges brought against him by the same writer.** We must not stop to answer the slanderers of Toussaint, for we shall scarcely have time enough even for the best and shortest answer to them, the record of his noble actions. The same libeller acknowledges, that, in appearance at least, piety is a ruling feature in the character of Toussaint. He reproaches him with being always attended by priests, and having had no less than three confessors. I wish

* This expression in the original is much stronger, but it savours too much of impiety to be quoted.

** Dubroca.

11

France had no worse priests than those who shared with this good chief all the perils and hardships of war on the mountains of St. Domingo, in order that they might soften and mend the characters of a new people by the powerful influence of religion.

But Toussaint's religion, the French atheists tell us, was all hypocrisy; so were his humanity, his moderation, his loyalty to the king, and afterwards, when the Convention had decreed freedom to his race, his fidelity to the Republic! Nay, his zeal for the cause of liberty itself, was all merely pretence and hypocrisy!

The strange vileness of Toussaint's hypocrisy consisted in this, that he all along was good it deeds as well as words. So deep was Tonssaint's hypocrisy, that the great Consul himself though a messenger from Heaven, "sent upon earth (as he tells us) to restore order, equality and justice," was grossly deceived by him, for he gave the highest praises to our hero down to the very day of setting a price upon his head, and only found out his hypocrisy, when resolved upon putting him to death. The truth is, that of all the man virtuesof Toussaint, his probity was the most distinguished. It was quite a proverb among our own officers, who long carried on war against him, and among the white inhabitants of St. Domingo, that Toussaint never broke his word.

There cannot be a better proof that he possessed and deserved this fame, than the reliance which was placed on his promises in the nicest cases by

12

those who knew him best, and to whom his falsehood would have been fatal; and it is a notorious fact, that the exiled French planters and merchants did not scruple to return from North America, and their other places of refuge, on receiving his promise to protect them. It is equally well known, that not one of them ever found cause in his conduct to repent of such confidence. Here may be introduced a short story, which will serve to shew how far Toussaint respected the principle of good faith, and with how good a grace the French government can question his probity.

It is well known that he entered into a treaty with General Maitland, the British commander-in-chief, by which the island was to be evacuated by our troops, and was to remain neutral to the end of the war. On this occasion, he came to see General Maitland at his headquarters; and the general, wishing to settle some points personally with him before our troops should embark, returned the visit, at Toussaint's camp in the country.

So well was his character known, that the British general did not scruple to go to him with only two or three attendants, though it was at a considerable distance from his own army, and he had to pass through a country full of Negroes, who had very lately been his mortal enemies. The Commissioner of the French Republic, however, did not think so well of the honour of this virtuous chief. It is very natural for wicked men to think badly of mankind, and the Jacobins not only suppose

13

every man will be bloody and treacherous when worth his while, but would probably hold him cheap if found of an opposite cast.

With such notions and feelings, Monsieur Roume the French Commissioner, thought this visit of General Maitland a good opportunity to make him prisoner; he therefore wrote a letter to Toussaint begging him, as he was a true Republican, to seize the British general's person. General Mail land proceeded towards Toussaint's camp. On the road he received a letter from one of his private friends, telling him of Monsieur Roume's plot, and warning him not to put himself into the Negro general's power; but the known character of Toussaint made the British general still rely upon his honor: besides, the good of his Majesty's service required at that period, that confidence should b placed in this great man, though even at some risk and General Maitland therefore bravely and wisely determined to proceed.

When they arrived at Toussaint's head quarters he was not to be seen. Our general was desired to wait, and after much delay the Negro chief still die not appear. General Maitland's mind began to misgive him, as was natural upon a reception seemingly so uncivil, and so conformable to the warning he had received. But at length, Toussaint entered the room with two letters open in his hand: "There general, (said the upright chief) read these before we talk together; the one is a letter just received from Roume, and the other my answer I would not come to you, till I had written my

14

answer to him; that you may see how safe you are with me, and how incapable I am of baseness." General Maitland read the letters, and found the one an artful attempt to excite Toussaint to seize his guest, as an act of duty to the Republic ; the other, a noble and indignant refusal. "What," said Toussaint, "have I not passed my word to the British general? How then can you suppose that I will cover myself with dishonor, by breaking it? His reliance on my good faith leads him to put himself in my power, and I should be for ever infamous, were I to act as you advise. I am faithfully devoted to the Republic, but will not serve it at the experience of my conscience and my honour."

It is not strange that with such virtues, and such talents, our hero should win the hearts of the Negroes, and soon become their favourite leader. He did so to such a degree, that their first famous chiefs were soon forgot; and except Rigaud, a brave and active Mulatto, leader in the south of the island, we afterwards heard nothing of any general of the Blacks but Toussaint Louverture. Rigaud was also a very able man; but not a man of principle, like Toussaint: he however pretended to be a. much more zealous friend of freedom than the other leaders; and distinguished himself by his rage against the planters and the English. By dint of his violence, he passed for a devoted friend of the cause, and long kept himself at the head of a large party, whom he persuaded that Toussaint was not so trust-worthy as himself; but he was at last forced

15

to yield to that great man's superior merit, and wale: driven from the island, because while there, he was continually disturbing the public peace.

When Toussaint first rose to power, the contest, between the Blacks and their former owners was ended, and the French Commissioners, who then attempted to govern the Island, acknowledged the freedom of the Negroes, and promised to maintain it. But another civil war arose, and was carried on with great fury between the party of the dethroned French king, and that of the Convention. In this the Negroes, as well as the White People, took different sides among themselves, and were perhaps about equally divided.

Toussaint, who knew that his brethren owed the Convention no thanks for their freedom, was naturally found on the same side with loyalty, generosity, and religion; and by the aid of his courage and talents, the cause of royalty was soon as triumphant in St. Domingo, as it had proved unsuccessful in Europe. For his great services in this war, he received from the king of Spain, a commission as general in his army, and had the honour of being admitted a knight of the ancient Military Orders of that country; so at least his enemies assert.

But events arose, which made it impossible for Toussaint, as a wise man and a true patriot, longer to refuse his adherence to the existing government of France. The cause of royalty having failed in that country, little could be done to serve the royal family by prolonging the miseries of civil war in a West

16

India island, while the great stake of Negro liberty might be lost by further opposition to the parent state. It was probably a deciding consideration with our hero, that the Planters and Loyalists of St. Domingo, with whom lie was now allied, began openly to intrigue for the assistance of Great Britain, and to invite us to invade the island; for their object, however friendly to French royalty, was certainly adverse to Negro freedom ; and it was less for the sake of restoring the sceptre of France to the Bourbons, than for that of recovering the iron sceptres of their own plantations, that most of these men desired to have the British flag flying at St. Domingo-they were staunch royalists then for the same reason that makes them now staunch friends to a Corsican usurper. Toussaint knew this, and saw that he must either make terms with the French commissioners, or engage himself on the same side with foreign invaders, and with Frenchmen who were sworn foes to the liberty of his race. For these and other reasons he found it necessary to give peace to the republican party whom he had already conquered, and to acknowledge the authority of the Convention.

From this time he was a faithful servant of France during every change in its government, though often molested and embarrassed in his plans for the public good by the folly and wickedness of the persons in authority in the mother country.

The Committees, Directors, and other successive Rulers of France from time to time, sent commissioners to the island; and these men were as fond

17

of plunder and confiscation in the West Indies, as their masters were in Europe. Every man who had property to forfeit, was sure to be cried down as a traitor. But happily in St. Domingo there was such a mind to check them as that of the generous Toussaint. This great man conducted himself with so much prudence, as, without giving offence to the French government, to make its commissioners mere cyphers. He suffered nobody to injure or insult them, and obliged every one to treat their office with respect, and yet left them no power, because lie found they would only use it for purposes of cruelty and mischief. He protected the planters from the commissioners, and both from the natural jealousy of the Negroes.

The French government more than once recalled its commissioners, and sent out new ones; but the case was still the same. There were among them very able men, but Toussaint was an over match for them all. They were obliged to leave in his abler hands all the actual power, and to lean on him for protection.

More than once his power and credit with the Negroes saved these men from destruction. General Laveaux in particular, once clearly owed his life to our hero, and publicly acknowledged the debt. Laveaux was at that time commander in chief for France; and the Negroes of Cape Francois, suspecting him of a plot against their freedom, rose against him, threw him into prison, and were preparing to put him to death, when Toussaint with a band of faithful followers marched into

18

the town and delivered him out of their hands. General Laveaux was on this occasion, so struck with the conduct and talents of Toussaint, that he did not scruple to declare, in a public letter, his resolution to take no measure in future in the government of the island, without that great man's advice and consent.

The French government could not but see that its authority in the colony depended wholly on the will of this noble African, yet was long foolish enough to attempt to govern there by other agents, till at length, in March 1797, they sent him a commission declaring him general in chief of the armies of St. Domingo. This commission he held under the express confirmation of Buonaparte, till Leclerc, fatally for France, and for himself, was sent out to supersede and betray this faithful servant of the republic.

It was a great mercy to many unfortunate white people who remained on the island, that a man like Toussaint possessed the chief power. He protected them from being massacred, and restored them to the property of which they had been deprived. When he found himself strong enough, and so well known to his followers as not to be afraid of slander, he even invited the banished planters to return from America, and other places to which they had fled for refuge; and such of them as returned, were restored by him to their estates.

There was one kind of property, however, for which our hero had no respect; and that was the property of human flesh and blood. When I say

19

therefore that the planters were restored to their estates, it must not be understood, that they were allowed to buy and sell their Negroes as formerly.

Neither did the Negro chief think it reasonable, that the masters should work their poor labourers as much, whip them as much, and feed them as little, as they thought fit. In these opinions there has been a wide difference between him and the Chief Consul; and the difference has cost Toussaint his life, and France the island of St. Domingo. Our hero however acted up to these sentiments, and therefore obliged the planters to put such of their former slaves as chose to work for them, on the footing of hired servants.

And here I must notice the greatest difficulty which Toussaint had to struggle with in his labours for the public good. The cruel and brutal method of driving, naturally makes the poor negroes regard their agricultural work with incurable dislike. Toussaint took unwearied pains to remove this difficulty, and to restore the tillage of the soil, upon which, under God, he knew that the happiness of every country chiefly depends. To this end, he encouraged the labourers by giving them a third part of the crops for their wages; a large compensation, in a country where sugar and coffee are the chief productions. He also made laws •to restrain idleness, and oblige people to labour upon fair terms for their own livelihood; and to enforce these laws, he made use of his power as a general.

Some people have fault with him, because

20

he did not employ the civil power for this purpose, instead of the military; but in truth he had no civil power to employ. People in this happy land are apt to forget, that laws, and magistrates, and courts of justice, all exactly fitted to produce peace, order public happiness, with the utmost possible regard to the liberty of the subject, are blessings that grow with the oak, and not with the mushroom. Human wisdom can no more make them on a sudden, or renew them in a moment when madly destroyed, than it can raise a tall tree in a single night from an acorn. As to Toussaint and his Negroes, they had every thing which belongs to civil life, to learn. In their former state they could know nothing of it; for a slave has no country; the breath of his master is his law, and the overseer is both judge and jury: the driver is both constable and beadle, as well as carman, to the human cattle. During the war, there was no place for any but military institutions; and Toussaint therefore, when it was necessary to enforce laws for the public good, had no officers of civil justice to whom he could resort.

It is true that for these reasons, he was obliged so far to disgrace the idle and disorderly Negroes, as to put them upon the same footing with the present free French republicans. The only difference between his government in this respect and Buonaparte's, was, that Toussaint had no dungeons, no sickly deserts of exile, nor any other organ of injustice or oppression. He put the idle vagrant, and the deserter, upon the same footing; and they

21

were equally liable to be punished after a fair trial by a court martial; but so mild were his punishments, that the severest one for a labourer, was the being obliged to enlist as a soldier.

There is one great branch of Toussaint's services to France, upon which an Englishman cannot like to enlarge. It is too well known what great pains we long took during the last war, to conquer St. Domingo. How much money, as well as how many valuable lives the attempt cost us, it would not be easy to compute. There is nothing in the conduct of our brave soldiers in that field, but what does them honour, yet I chuse to be silent as to that unhappy attempt, and shall only say, that Toussaint through the whole of the long contest with our army, acted so as to win the admiration of his enemies as well as the praise of his ungrateful country.

Here I shall beg leave again to quote from the words of the Consul's champion, Dubroca. "His conduct during the war with the English was brilliant and without stain, and that epoch of his life would be truly great, if the services he render the republic at that time, had not been like all that preceded, subservient to his own ambition." That a defender of the Consul durst venture to speak ambition as a crime, is strange, but perhaps the only guilty ambition in Buonaparte's judgment, is that which aims to promote liberty and social happiness.

I pass to the evacuation of the towns and for of the island by his majesty's troops. Here the French assassins of Toussaint make their chief stand against him. "He suffered the English to

22

escape; say they, on too easy terms, and his conduct upon this occasion, was treachery to the republic."

How happens it that Toussaint's treachery was' not found out in France a little sooner? The terms of the convention between our commanders and him, were no secret; and yet down to the moment of General Leclerc's attack upon this brave man in the field, he was treated by the French government as one of its most faithful and deserving subjects.

The Consul sent him a letter last year --a treacherous one I admit, but not the less fit to be quoted against himself upon this point of Toussaint's character. Of this letter, General Leclerc was the bearer, and the following are some of its expressions. "We have conceived for you esteem, and we wish to recognize and proclaim the great services you halve rendered to the French people. If their colours fly on St. Domingo, it is to you and your brave Blacks that we owe it. Called by your talents and the force of circumstances to the chief command, you have destroyed the civil war, put a stop to the persecutions of some ferocious men, and restored to honour the religion and the worship of God, from whom all things come."*

After composing encomiums like these, and even printing them in his gazette, can any thing exceed the effrontery of the Consul in afterwards

* Dispatches of Leclerc of February 9. Moniteur of March 21, 1802.

23

stigmatizing this great man as a traitor for action committed before the letter was written?

I will not detain my readers with stating and answering some other charges which the murderer of Toussaint have lately brought against him o account of his treaty of neutrality with General Maitland, and the constitution which he afterwards framed for St. Domingo with the consent of a general assembly of the people; for though it won] be easy to chew that both these measures were n4 only guiltless, but such as redounded greatly to his honour, the proof of these truths would require some views of the state of St. Domingo and France, which cannot be given in a small compass; and the preceding confessions under the hand the Consul, are surely enough to repel all charges of disloyalty against our hero down to the period Leclerc's invasion.

Yet as to the constitution, I beg leave to add farther extract from the same official letter of Buonaparte: -- "The situation in which you we placed, surrounded on all sides by enemies, and without the mother country being able to succour or sustain you, has rendered legitimate the, articles of that constitution which otherwise would not be so."

Toussaint being relieved from the pressure the war with England, set to work with new vigour in his plans for the public good.

The restoring the public worship of God, a spreading the knowledge of religious truth as far he himself was blessed with it, were the objects

24

nearest his heart. Next to these, which he knew be the corner stones of public happiness, he was unwearied in his attempts to reform abuses ; especially to set the idle to work, and by these and other means to improve the culture of the soil, and encourage that foreign commerce, which is so necessary to a West India island.

It is truly wonderful to think how much toil he must have gone through, even in the little we know of his public labours; for he had still from e perverseness of Rigaud's party a new insurrection to quell, and had to obtain possession of the Spanish part of that large island lately ceded to France, which the Spanish governor, upon various pretences, and perhaps by the secret request the French government, long withheld. But at length the genius and activity of our Hero triumphed over all obstacles; and before peace was concluded between this country and France, every part of St. Domingo was in quiet submission to his authority, and rapidly improving in wealth and happiness under his wise administration.

So rapid was the progress of agriculture, that it s a fact, though not believed at the time in England, that the island already produced, or promised yield in the next crop, one third part at least of large returns of sugar and coffee as it had ever en in its most prosperous days. This, considering all the ravages of a ten years' war, and the great scarcity of all necessary supplies from abroad, is very surprising, yet has since clearly appeared to be true.

25

But what was of far more consequence, this great and growing produce was obtained without the miseries, the weakness, or dangers of West India slavery. Men were obliged to work, but it was in a moderate manner, for fair wages; and they were for the most part at liberty to chuse their own master. The plantation Negroes were therefore in general, contented, healthful, and happy.

A still more happy effect had arisen from the new state of things; a blessing of the greatest importance to France, if she had not been mad enough to take the wicked measures of which I shall soon have to speak; and not to France only, but to Africa, and to human nature. The effect I speak of, was a large increase in the rising generation of Negroes, instead of that dreadful falling of which is always found in a colony of Slaves.

My readers may be surprised at this fact, especially if they have ever met with any of those false and idle accounts which have been published, to persuade us that the loss of life among the island Negroes, does not arise from oppression. "What, it may be said, can the young and infant Negroes of St. Domingo have increased by natural means since the revolution, in spite of perpetual war, foreign and civil, of frequent massacres, and of all the wants and miseries which, during twelve years, have fallen upon that hapless and devoted Island? How can this be, when in Jamaica, and other West India Islands, in the midst of peace and plenty, the same race of people are always declining

26

in numbers, so that population can only be kept up by the Slave Trade ?"

I leave the defenders of slavery and the Slave Trade to answer the question. I will only offer for their help, the opinion of a person whose judgment and impartiality they will readily admit. It is no other than Monsieur Malouet, formerly Minister of the French Colonies and Marine, an old West India Planter, and a defender of the Slave Trade.

M. Malouet published a book last year at Paris, in which he attempts to justify the Consul for reenslaving the Negroes in the West Indies; yet thus he writes of the state of Negro population in St. Domingo: "ALL ACCOUNTS ANNOUNCE A MUCH GREATER NUMBER OF INFANTS, AND LESS MORTALITY AMONG THE LITTLE NEGROES THAN THERE WERE BEFORE THE REVOLUTION; WHICH IS ASCRIBED TO THE ABSOLUTE REST WHICH WOMEN BIG WITH CHILD ENJOY, AND TO A LESS DEGREE OF LABOUR ON THE PART OF THE NEGROES. **

Such then were the happy prospects at St. Domingo, when the peace with England unchained the French navy, and left the Consul at liberty to carry to the new world, the same scourge with

* War and massacre will too fully account for there being on the contrary, a decrease among the men. If the ravages of disease, usual in slave colonies, had been added, not a man fit to bear arms could have been left.

** Malouet Collection de Memoires sur les Colonies, Tome IV. Introduction, p. 52.

27

which his fierce and ambitious temper had long afflicted the old.

As soon as peace was concluded with England, the French Consul dispatched a fleet to St. Domingo, commanded by Admiral Villaret, with an army of at least 20,001 men. At the head of the army was placed General Leclerc, the Consul's brother in law, assisted by several Generals of great note, particularly Rochambeau, well known in the West Indies for his attachment to the cause of slavery. In this expedition the main object of Buonaparte was to wrest from the Negroes their newly acquired freedom, and to reduce them to their former state of servitude, and so confident was he of the attainment of this object, that he sent over his brother Jerome with the armament, that be might pluck the laurels which it seemed destined to acquire. The Consul did not however rely on force alone, for the accomplishment of his purpose. He was aware of the importance of securing the cooperation of Toussaint, and was determined if possible to win him over.

As our hero, however, had already the principal authority in St. Domingo, and had long been commander in chief and governor there, by commission from the government of France, Buonaparte felt that the honours and rewards he had to offer, might perhaps not be a sufficient price to the Negro general, for treachery to his brethren. He therefore devised an expedient more likely to ensnare this great man's feelings; and this was to put his two

28

beloved sons on board the fleet, as hostages for the father's conduct.

These youths had been sent by Toussaint to France, for their education. He had trusted them; to French honour and gratitude; and it would move the coldest hearts to read the letter in. which he anxiously recommended them to the care and protection of the government. At every line one might imagine the fond father's tears dropping on the paper; nor is its piety less striking than its tenderness, for the chief request made in the letter, was that they might be brought up in the fear of God, and the knowledge of religion. Unfortunate Toussaint! little did he then know to what keeping; he consigned them !

To take these youths from their studies, and send them out to inveigle their father, was the project of, Napoleon. He has no children, or his heart, cold and hard though it is, might have checked him in so vile a purpose. To feel its baseness fully, a fact should be known, which is true beyond all reach of doubt, though this is not the place for its proof, that if Toussaint had yielded to the temptation, it would have been immediately fatal to him; the, fixed design in that case, was to tear him in a few, days from these, dear bought children, and put him to death. The Consul had fully resolved, that when he should have got the chiefs of the free Negroes in the West Indies into his power, either by force or fraud, they should not live to oppose his tyranny in future; witness his treatment of Pelage, the Toussaint of Guadaloupe, who joined

29

the French General Richepanse, and by prodigies of valour at the head of his black troops, reduced the island to submission, relying upon the solemn promises of the Consul to maintain the general freedom of the blacks; yet his reward was to be seized by surprise, with all his brave officers, and either sold as slaves for the Spanish mines in Peru, or, as is more probable, drowned at sea. Certain it is, they were carried by shiploads to sea, stowed like sheep in a pen, and heard of no more. But the history of the Consul's unparalleled wickedness at Guadaloupe, may be the subject of a separate book.

Strong though Buonaparte's hopes were, of succeeding by these virtuous means at St. Domingo, and making of Toussaint, first a vile instrument of his tyranny, and afterwards its certain victim, he was resolved to have other expedients in reserve. He took extreme pains, therefore, and with too much success, to take the Negro chief unawares, so that if found faithful, and clear-sighted in the cause of freedom, he might be the more easily crushed by arms.

To this end, the Consul loudly professed for our hero and his Negroes, the utmost admiration, gratitude, and esteem, wrote him letters full of praises and promises, and confirmed the commission of commander in chief which he held under the last and former governments of France. Far from avowing himself an enemy to the liberty of the Negroes, this hypocrite pretended to be as fond of it as Toussaint himself. He went so far as to lay before

30

one of the public bodies in France, after the peace, and to publish in his gazettes, a plan which he pretended to have formed for the government of the French colonies, in which he solemnly declared, that the freedom of the Negroes should be maintained in every colony wherein it then existed; and excused himself for not immediately putting on the same footing, the slaves of Martinique and other places just restored to him by the peace, on account of the great and unavoidable evils of such a sudden :revolution. “It would cost too much," said this matchless impostor, "to humanity!"

To the same deceitful ends, he kept on foot that .law of the republic, by which the Negroes were all solemnly declared to be free French citizens. Nor did he revoke this solemn law, confirmed by his own constitution, and paid for by the West India Negroes by the most essential services to the republic, till full three months after he had publicly avowed to the British admiral at Jamaica, that his expedition was sent out to restore the old system of bondage, and had begun accordingly to murder the Negroes by thousands and ten thousands, in hot blood, and in cold, for not submitting to become slaves again, at his own imperious bidding.

Toussaint then, was the more easily deceived, by supposing that in addition to every principle of honour, justice, gratitude, and mercy, that can rind a nation, he had some security in the laws of the republic, and in the Consul's own constitution, as confirmed .by his solemn oath.

31

But, lest the news of the great armaments that were preparing, should, in spite of all this, put the Negro chief on his guard, means were found to deceive him grossly, both as to the amount of the force, and its destination. We are not yet informed what arts were used for this purpose; but certain it is, that Toussaint expected only such a squadron and such a body of troops as the French government might naturally send in time of peace, for the use of a loyal colony. He supposed them to come only with friendly views, and by proclamation enjoined the Negroes to receive them with affection, confidence, and respect. He made no preparation whatever for defence, not even so much as to give the necessary orders to his subordinate generals who commanded in the towns on the coast. Such advantage had the Consul from his frauds; as if on purpose to skew in the event, how impossible it is to bring back free men to cart-whip slavery, and to make the folly of the purpose, as glaring, if possible, as its baseness.

While Toussaint was working night and day for the good of France, by restoring with all his might the tillage of her richest colony, the French fleet and army were stealing over the sea to destroy him and his useful labours. They at length arrived, and it might be supposed perhaps that the first step of General Leclerc was to send notice of 'his arrival to the lawful governor of the island, whom he was sent to succeed, and demand peaceable possession of the town and forts in which he meant to quarter his forces. No such thing.

32

General Leclerc went to work exactly like an invading enemy in time of war, though he had the modesty afterwards to complain, that he was not `'received as a friend. The moment he saw the coast of St. Domingo, he broke his force in three divisions, which fell like a sky-rocket, as nearly as possible at the same time, on the three principal towns of the island. Nothing could be better contrived.

At Fort Dauphin, where General Rochambeau arrived with the first division of the army before the two others could get round to their points of attack, the troops were instantly landed. No summons was sent to give the poor wondering colonists a chance of saving their lives by submission. The troops were drawn up in battle array, on the beach. The Negroes ran down in crowds to behold so strange a sight, and before they had any notice of what was designed against them, they were charged with the bayonet, and routed with the loss of many innocent lives.

So horrible a proceeding might not be believed, if it came from any other authors than the butchers themselves. It is true the Negroes are said to have called out

"no white men," but if so, it only confirms the cruelty of so abrupt a proceeding; during ten years they had seen no white soldiers but enemies, bent on their destruction, It is true also, that General Rochambeau says, he made "signs of fraternity" to the blacks before he attacked them; but these poor creatures were no doubt as much at a loss for the meaning of such pantomime mummery

33

as of the invasion itself. The most ignorant inhabitants of Europe indeed know too well now what it signifies; but the Negroes, not having seen this Jacobin free-masonry before, could not know that signs of fraternity were sure forerunners of a massacre, till the bayonet reformed their ignorance.

While by such means possession was obtained of Fort Dauphin, the main body of the fleet and army under Villaret and Leclerc were hastening round tom the Cape. They arrived the next day, and instantly prepared to land and take possession of the town; but Christophe, the black general, who commanded at this important post, having heard no doubt of the massacre at Fort Dauphin, bravely and loyally refused to suffer them to enter the harbour until he should receive orders from Toussaint. I say "loyally," for Toussaint, who was his: lawful superior; was absent in the interior country, and Christophe only demanded time to send to him and receive his commands. His ruffian enemies have railed him for this; but every good officer will approve his conduct. Indeed they were so conscious that the refusal was proper, as to endeavour to excuse their own violence by a palpable lie. They pretended to suspect that Toussaint was really in or near the town, and that his absence was only a pretence to gain time, though the contrary is manifest from what it afterwards stated in their own

gazettes. The truth is, they resolved to profit by Toussaint's absence, and therefore landed troops by force; under cover of the ships; at the

34

expence not only of many lives, but of the destruction of the town.

They have violently abused the brave and faithful Christophe for setting fire to this place, which, in his feeble and unprepared state, deserted as he was by all the white inhabitants, it was impossible for him to defend. But he had repeatedly warned the invaders that he should find it his duty thus to act, if they persisted in forcing a landing, without giving him time to send to his commander-in-chief ; and what reasonable man or good soldier will blame him for keeping his word? What! was he to leave these good quarters behind him for lawless invaders to lodge themselves in, and thereby the better effect their perfidious and bloody designs In the way they acted, they were entitled to the same reception in St. Domingo, as I trust they would meet in England ; and were it necessary to burn Dover to prevent French invaders from fixing in it, I hope no English governor would scruple to kindle the fire.

Another act, indeed, was half charged upon Christophe, which nothing could have excused. It was said in the first French accounts, that he had threatened to massacre the white inhabitants ; and the Consul's gazette left it, with the usual fair dealing of that paper, to be supposed that this threat had been carried into effect. But the only voice which has been allowed to speak from the bloody stage of St. Domingo, that of the French government itself, has since fully cleared the Negro chief from this suspicion. The inhabitants, to the amount

35

of 2000, were carried off indeed as hostages, but not a man was put to death. This is particular; worthy of remark, as it will soon be seen how of polite was the conduct of the French army, the only savages in this war, at least while Toussaint commanded.

Yes! by the French generals themselves, who avow that from the beginning of this war they gave no quarter, it is recorded to their own deathless infamy, that not a white man, among the many who upon this occasion fell into the hands of the Negroes, found an enemy like the hero of Jaffa. "No person was killed at the Cape” *. “More than 2000 inhabitants of' the Cape, who were the most distant mornes, have returned” ** Such are their very words. During three months the men must have been in the power of the Negro chiefs; and during the same period General Leclerc, "the virtuous Leclerc," as his brother-in-law stiles him, had been putting Toussaint's soldiers to death, in cold blood, as often as they fell into his hands I.

Time will not admit the detail of the proceedings in the other parts of the island; it is enough that they were of the same complexion with those which have been already noticed, and that everywhere the French refused to give the chance of saving bloodshed, by allowing the astonished Negro officers time to send for orders to their

* Account in Paris gazettes of 1st Germinal, (March London newspapers of March 29.

** Leclerc's official letter of May 8th, in which he gives count of the pretended surrender of Toussaint.

36

commander-in-chief. Everywhere they demanded instant possession of the forts, and every-where punished the proper refusal by as much murder as they were able to commit. As all these places were exposed to the cannon of the ships, and were quite unprepared for defence, the French succeeded so far as to oblige the Negro troops to retire, but not till after some brave resistance.

All this while, for the whole was done in about forty-eight hours, Toussaint was in an inland part of the island, at too great a distance from the coast to give any timely assistance or orders at either of the points of attack.

The time was now come to try the force of corruption upon the mind of this African patriot. The first game had been played with success up to the Consul's wishes, except that Cape Francois had been burnt. The chief posts on the sea had been surprised and taken according to his merciless orders ; the next point, therefore, was to win over Toussaint, if possible, now that he could be treated with safely; for to attempt it sooner, would have been to put the important advantage of surprise at the hazard of his virtue. Accordingly an ambassador was sent to him from the smoking ruins of Cape Francois, and the man chosen for the errand was Coisnon, the tutor of his sons.

This man, as low in morals, as from his office we may suppose he was high in learning, was probably sent from France for the purpose of this vile attempt on the father of his pupils. I doubt not he had his lesson from the lips of the Consul himself.

37

With him were sent the two youths, the one I believe about seventeen, the other probably fifteen, years old, who both had been separated seven or eight years from their affectionate parents, and were now doubtless much improved, not only in stature, but every other point of appearance that could rejoice the eye of a father. Ignorant as the poor lads were of public affairs, they had been taught that it was for their father's good to comply with the wishes of the Chief Consul; and Buonaparte himself had talked with and caressed them at Paris, in order to impress that opinion on their minds.

With these innocent decoys in his train, and with letters both from General Leclerc and the Consul, full of the most high flown compliments to Toussaint, and the most tempting offers of honours, wealth, and power, Coisnon set out from the Cape, and proceeded to the place of our hero's usual abode. His cruel orders were to let the boys see and embrace their father and mother, but not to let them remain: If the father should agree to sell himself, and betray the cause of freedom, he was to be required to come to the Cape to receive the commands of Leclerc, and become his lieutenant general; but if he should be found proof against corruption and deceit, the boys were to be torn from his arms, and brought back again as hostages. If nothing else could move him, the fears and agonies of a parent's breast might, it was hoped, be effectual to bend his stubborn virtue.

"But how," some of my readers may be ready

38

to ask, "was Coisnon to be able to bring them back against Toussaint's inclination? What force had he to employ against the Negro chief in the country?" I answer, a force which his base enemies well knew the sure effect of on his noble mind, the force of honour. A safe conduct was obtained from Toussaint, or his lieutenant-general; and the sacred faith of a soldier, whose word had never been broken, was engaged for the return both of the envoy and his pupils.

That vile tool of the Consul proceeded with the boys to Toussaint's house in the country, which was a long day's journey from the Cape; but on their arrival, the father was not at home, his urgent public duties having called him to a distant part of the island, where he was probably endeavouring to collect his scattered troops, and to make a stand against the invaders. The mother, however, the faithful wife of Toussaint, was there; and let my readers judge with what transports of tender joy she caught her dear long-absent children to her bosom. The hard-heated Coisnon himself says, "This good woman manifested all the sentiments of the most feeling mother.” *

It was no hard task for the envoy to delude this tender parent. He professed to her, as he had declared to all the Negroes he met with on his journey, (so he has not scrupled to confess under his own hand), that the Consul had no design whatever against their freedom, but wished only for

* See Coisnon's report to the French ministers London papers of April, 1802.

39

peace, and a due submission to the authority of the Republic. The fond mother was ready to believe all he said. She ardently wished that it might be true, and that her beloved husband, with his superior knowledge and judgment, might see cause to confide in these pleasing assurances. The envoy has, unluckily for the cause of his employers, made it clearly appear in his account of this embassy, that if Toussaint had any object beyond the freedom of himself and his brethren, it was unknown to, and unsuspected by, the wife of his bosom. She instantly sent off an express to him to let him know that a messenger from the Consul was come, with the offer of peace, liberty, and their children.

Toussaint was so far distant, that with all his wonderful speed in riding he did not arrive at Ennery (that was the place of this interesting home) till the following night. Ah! what pangs of suspense, what successions of hope and fear, must have wrung the heart of the poor mother in the interval! But her beloved husband at last arrives, and rushes into the arms of his children.

For a while the hero forgets that he is any thin but a father. He presses first the elder boy, then the younger to his heart, then locks them both a long embrace. Next he steps back for a moment to gaze on their features and their persons. Isaac, the elder, is so much grown that he is almost tall as his father; his face begins to wear a man air, and Toussaint recall in him the same image that sometimes met his youthful eyes when he

40

bathed in the clear lake among the mountains. The younger is not yet so near to manhood, but his softer 'features are not less endearing. The father sees again the playful urchin that used to climb upon his knees, and the very expression that won his earn in the object of his first affection. Again he catches both the youths to his bosom, and his tears drop fast upon their cheeks.

Let not my readers suppose this account is founded wholly on conjecture. Even the cold-blooded Coisnon himself thus far in effect draws back the curtain, and opens the first scene of the tragedy in which lie was an actor. The miscreant seems to value himself upon his firmness in pursuing his game unmoved by so affecting a scene; for thus he writes of it to his employers: "The father and the two sons threw themselves into each others arms. I saw them shed tears, AND WISHING TO TAKE ADVANTAGE OF A PERIOD WHICH I CONCEIVED TO BE FAVOURABLE, I stopped him at the moment when he stretched out his arms to me, &."How striking is the picture here presented! A virtuous and amiable hero is at the crisis of his fate; a fond father is pouring out the tears of manly sensibility ever his long absent children. He stretches out his arms with an emotion of ill-placed gratitude to the tutor of their youth, when the same tutor, bent upon seducing him to his infamy and ruin, craftily seizes this moment as the most favourable for his treacherous designs! Nature has tender sympathies which even the cruel cannot well resist. There are situations in which even a ruffian cannot well

41

avoid being turned by pity from his purpose. But these agents of the atheistical Consul seem to be pity-proof in all cases.

Coisnon, retiring from the embrace of Toussaint, assails him in a set speech with persuasions to submit to the Consul, and to betray the cause of freedom. He does not perhaps desire him in plain terms to permit slavery to be restored; on the contrary protests that there is no such design; but Toussaint knew too well the meaning of such professions; and that his discerning mind on this point should be so imposed upon, after what had happened, could hardly be expected either by the envoy or his masters. Such speeches, if used to Toussaint himself, were probably meant only to say his credit, and give him the means of deceive his followers. He was in effect desired to come the Cape and bring over his troops to join the French standard. On this condition he was assured of

"respect, honours, fortune," the office of the lieutenant-general of the island," all in short that the gratitude of the republic could offer, or his of heart, desire. On the other hand, if he should refuse to submit, the most dreadful horrors and series of war are denounced against him and followers. The implacable vengeance of the great nation is threatened; and the eloquent envoy does not omit to point out to him how hopeless must be

42

all his efforts to resist the armies which have conquered Europe, and which now will have no enemy contend against, but the rebels of St. Domingo. Above all, he is desired to reflect upon the fate that awaits the hostage youths, so beloved, and so worthy of his affection. "You must submit," said Joisnon, "or my orders are to carry my pupils back to the Cape. You will not, I know, cover yourself with infamy by breaking faith and violating a safe conduct. Behold, then, the tears of your wife; and consider, that upon your decision depends whether the boys shall remain to gladden her heart and yours, or be torn from you both for ever"* The orator concludes by putting into the hero's hands the letters of the

captain-general and the Consul.

Isaac next addressed his afflicted father in a speech which his tutor had no doubt assisted him in preparing. He related how kindly he was received by the Consul, and what high esteem and regard that chief of the republic professed for Toussaint Louverture and his family. The younger brother added something which he had been taught to the same effect; and both, with artless eloquence of their own, tried to win their father to a purpose, of the true nature and consequence of which they had no suspicion.

* I desire not to be understood as giving the exact language of this conference throughout; but the substance is either expressly avowed in, or plainly to be inferred from, Coisnon's report, and other official papers.

43

Need we doubt that the distressed mother added her earnest entreaties to theirs?

During these heart-rending assaults on the virtue and firmness of Toussaint, the hero, checking his tears, and eying his children with glances of agonized emotion, maintains a profound silence. "Hearken to your children," cries Coisnon. "Confide in their innocence; they will tell you nothing but truth."

Again the tears of the mother and her boys, and their sobbing entreaties, pour anguish into the hero's bosom. He still remains silent. The conflict of passions and principles within him may be seen in his expressive features, and in his eager glistening eye. But his tongue does not attempt to give utterance to feelings for which language is too weak. Awful moment for the African race! Did he hesitate? perhaps he did. It is too much for human virtue not to stagger in such a conflict. It is honour enough not to be subdued. But why do I speak of human virtue? The strength of Toussaint flowed from a higher fountain; and I doubt not that at this trying moment he thought of the heroism of the Cross, and was strengthened from above.

Coisnon saw the struggle, he eyed it with a hell-born pleasure, and was ready in his heart to cry out "victory," when the illustrious African suddenly composed his agitated visage, gently disengaged himself from the grasp of his wife and children, took the envoy into an inner chamber, and gave him a dignified refusal. “Take back my children,"

44

said he, "since it must be so. I will be faithful to my brethren and my God."

Can any trait that History has recorded of the patriot or the hero be put in competition with this noble sacrifice to public duty!

Coisnon, finding he could not carry his point, wished at least to draw our hero into a negotiation with general Leclerc; and Toussaint, always humane and fond of peace, was willing to treat upon any terms by which "the horrible fate," as he himself truly called it, which was intended for his brethren, might be avoided without the miseries of war. He, therefore, readily agreed to send an answer to the captain-general's letter, but would not prolong the painful family scene by staying to write it at Ennery, or again seeing his boys. It was two in the morning when he arrived there, and at four he mounted his horse again, and set off at full speed for his camp.

On the next day our hero dispatched a Frenchman of the name of Granville, who was tire tutor to his younger children, with a letter for the captain-general; and this man, whom Coisnon is anxious to prove as great a rogue as himself, overtook his brother-tutor and the two poor hostage youths on their way to the Cape.

On the parting between the mother and her children, as it afforded no room to display his own talents at negotiation, the envoy has been prudently silent; but such of my readers as have feeling hearts will be able to paint it in some degree for themselves. Toussaint's letter was of such a nature that it

45

produced a reply from general Leclerc, and a further correspondence took place between these opposite leaders during several days, a truce being allowed for the purpose, which Leclerc expected as he tells us, would have ended in a peace.

It would be most desirable to have recourse to the letters that passed on this occasion ; but Leclerc and the Consul have not thought fit to publish any of them; and as to Toussaint he had no the means of publication; for when his enemies took the towns, his printing presses all fell into their hands ; and, then, not a letter was sufferer to pass from the island, or any news from thence to be told, without leave from the Consul or his generals. We must be content therefore with such intelligence as they have thought fit to give us.

The treaty at length broke off, and we are to] it was in consequence of a discovery manifest] made in Toussaint's letters, that he was a hypocrite, and only treated in order to gain time. What was the nature of his demands the French Government did not think proper to state. In absence of all information on this head, I will leave to suppose, that the liberty of the common people, with some security for that blessing, the points in dispute, as they were the only things they would not yield, and were all that Toussaint sought to obtain. The only light which Leclerc’s real or pretended dispatches give to assist guesses respecting the nature of this negotiation is reflected from his reason for putting and end to it. "My orders," says he "are immediately to

46

restore prosperity and abundance." Now it must be presumed that the only means proposed for effecting this miracle was the cart whip; and that Toussaint would have objected to no other means of making the island prosper, his former conduct sufficiently proves.

The truce being ended, war was most furiously renewed against Toussaint and his adherents in every quarter of the island; and that general and Christophe were by proclamation declared to be "out of the protection of the law."

General Leclerc took, however, other steps far more effectual to him in the war than this ferocious proscription of the chiefs. He saw that it was easier to dupe the poor labourers, than to deceive men who had been accustomed to govern; he knew that the poor in all countries are apt to be discontented with their rulers, when they feel the public evils, which a war, necessary even for their own sakes, must always produce ; and he also knew, that the labouring Negroes, who were there called cultivators, had in general been loth to submit to necessary industry, and were but half content with Toussaint for putting by his laws, a curb upon idleness and vice. He therefore concluded, that it would not be impossible to make a breach between the upright chief and the cultivators; or, at least, to make the latter mere bye-standers in the war.

With this view, he, in the first place, forbore to attempt any change in the state of the labouring Negroes in the places occupied by his troops.

47

Though he had many of their old masters in his train, to whom the Consul had vowed that he would restore their slaves, and put the cart-whip soon again in their hands, Leclerc did not suffer one of them to go upon his own estate; or only allowed them to go to confirm the new order of things, and treat the labourers as free men. Not a whip was to be seen or heard for some time on any account. But he went much further. He published in his own name, and the Consul's name, solemn declarations, that the freedom of all the people of St. Domingo should be held sacred. In the same papers he taxed Toussaint, and the soldiers who followed him, with ambition, and threw on them the blame of all the dreadful sufferings that were going to fall on the colony.

It is not to be wondered at, that the French invaders should use these arts. In what country that has fallen under the dreadful yoke of the republic has not the same game been played in the beginning, as far as the state of the poor would allow in this instance the extreme ignorance of the cultivators rendered it, with regard to them, peculiarly successful.

But Leclerc also assailed, with too much success, the fidelity of the soldiers, and of the black generals and officers who had commands under Toussaint. He held out to them the most tempting offers of preferment in the French service, if they would join his army; and two or three traitors who came over to him on his first landing, were promoted to the highest commands, and caressed

48

most flattering manner. He did not scruple to bind himself to every Negro general who would pit his word, not only for the freedom of himself his corps, but that of all the Negroes in the island. There still remained there great numbers he old party of Rigaud; and though these were zealous friends to freedom, and very suspicious of white people, yet they hated Toussaint, because he had conquered and expelled their old leader; and they were therefore among the first to listen the false assurances of Leclerc, and lend him heir aid against their countrymen.

It was more by these base means, than by the bravery of his troops, that Leclerc obtained all his early successes, of which the French government so loudly vaunted itself, early in the summer of last year. It must be admitted that his French troops fought bravely, and with astonishing activity and perseverance, considering their disadvantages in that country; but, if they had not been powerfully assisted by Negro allies, and if the cultivators had not been so infatuated as for the most part to resist the earnest calls of Toussaint, and remain quiet spectators of the war, the invaders would never have been able to advance far from the coast.

It is no part of my undertaking to write the history of the war of St. Domingo. It could else very easily be shewn from the French gazettes, that whenever they engaged the Negroes successfully, the latter were inferior in numbers, or at least in regular troops, as well as in arms. It could

49

also be proved from the same accounts, that in spite of that inferiority, Toussaint's troops more than once defeated the invaders. In a war in which the gazettes are all on one side, the accounts of the publishing enemy should be very strictly watched; and yet, with a common degree of attention, any readers of Leclerc's dispatches will find that these assertions are entirely true.

The courage of Toussaint in this war, as in all the former ones in which he had been engaged, was conspicuous. The only engagement with troops led by himself into action, of which his enemies have thought it prudent to speak, was the battle of the Ravine of Couleuvre, and of this action Leclerc gives the following account: "A combat of man to man commenced, -- the troops of

Toussaint fought with great courage and obstinacy; but every thing yielded to French intrepidity." He adds, indeed, that Toussaint evacuated a very strong position, and retired in disorder to Petite Riviere, leaving 800 of his troops dead on the field of battle. But let us remember that this 'is the French account, and that Toussaint's story is untold*.

Our hero's spirit was still more honourably displayed in his constancy and firmness. So powerfully did the dreadful scourge of war, inflicted upon all points of the colony at once by France and her numerous black confederates, second the

* See Leclerc's official dispatches of. February 27. London papers of April 19,

1802.

50

treacherous offers and promises of Leclerc, that such of the Negro troops as still adhered to Toussaint began to be weary of the contest, and every day almost, some leading man among them went over to the enemy. From the first, the regular troops he was able to collect were not very numerous: as it appears even from the accounts of his enemies, who certainly could not wish to represent the force they had been opposed by, as less than it really was. So many of the military Negroes had been induced to join the French, or at least to lay down their arms, and so great a proportion of the rest had been killed in action, that the black generals, by the end of the month of February in which the war began, were chiefly supported by such of the cultivators as the influence of Toussaint could preserve from the deceits of Leclerc, and engage to fight in the case of their own freedom.